|

| View of Montreal from Pointe-à-Callière, museum, 2017 |

Here is the complete (unedited) text of my interview with

Poetry Quebec from January 2010.

--------------------------

Interview with Stephen Morrissey

1. Are you a native Quebecer? If not, where are you originally from? Why did you come to Quebec?

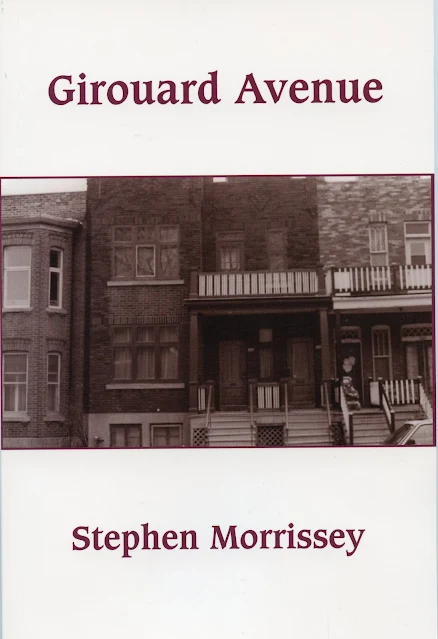

I was born in Montreal in 1950. My family moved from Ireland to New Brunswick around 1837 and my great great grandfather, Lawrence Morrissey, moved to Montreal from New Brunswick a few years later. On my mother’s side, John Parker, my grandfather, moved here with his wife and young son around 1910 from Blackburn, England, and he worked as a fireman with the City of Montreal. I’ve researched and written my family’s history, and this can be found at www.morrisseyfamilyhistory.com. Some poems written out of this research are in Girouard Avenue (forthcoming fall 2009), my new book of poems. My paternal grandmother lived at 2226 Girouard Avenue in N.D.G. for about forty years and, for me, it represents a psychic center that I often visit in dreams.

2. When and how did you encounter your 1st Quebec poem?

When I was a student at Monklands High School in the mid-1960s, I studied North American Literature with Mr. Dewdney, who was a terrific teacher. This course was mostly, if not all, Canadian literature, and we read poets and some fiction writers (for instance, Stephen Leacock) from the 19th and 20th Centuries. I loved the writing we studied and the poems of Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and Charles G.D. Roberts have stayed with me all this time. We read Earle Birney’s “David,” one of the greatest Canadian poems. There were also English Quebec poems in the course textbook, A Book of Canadian Poems, An Anthology for Secondary Schools (McClelland and Stewart, Toronto, 1963), which was edited by Carlyle King, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan, and of which I still have a copy. I always took for granted the importance of Canadian literature since we studied it in school; and there were always poets and writers living in our community. The first Quebec or Montreal poem that really made an impression on me, that really touched me deeply, was A.M. Klein’s “Heirloom.” Later, I wrote a poem of my own, influenced by Klein’s poem. I used his title, and included it in my first book, The Trees of Unknowing (Vehicule Press, 1978). I was very impressed when I saw Endre Farkas’s play on Klein, Haunted House, at the Segal Centre for the Performing Arts, in the winter of 2009. Farkas’s play portrayed Klein’s life and showed how important Klein was to the development of Canadian poetry.

3. When and how did you first become interested in poetry?

Even when I was young I knew of Irving Layton and Louis Dudek. I remember they had a public falling-out that was in the newspapers, in letters to the editor, in the early 1960s. Max Layton, Irving’s son, was a student at West Hill High School with my older brother. I used to walk along Somerled Avenue to Willingdon School where I was a student. I would pass an apartment building I had heard was owned by Irving Layton. Montreal poets were famous nationally. F.R. Scott was a law professor at McGill University, a constitutional lawyer, and one of the founders of the CCF. He was widely known for his successful 1959 Supreme Court defense of Frank Roncarelli against the Quebec government. The premier of Quebec, Maurice Duplessis, intervened to deny Roncarelli, a Jehovah’s Witness, his legal rights. Scott’s intervention saw the eventual reinstitution of Roncarelli’s civil rights. However, I believe poetry was F.R. Scott’s passion and it is primarily for his poetry that he is remembered.

Are poets born or are they created from the experiences of their lives? I think, in my case, it’s a combination of both. I always loved to write, especially poetry, but perhaps I was also driven to write by the circumstances of my life. Had I been more extroverted I may not have become a poet; perhaps introverts naturally gravitate to solitary activities, like writing poetry. I began writing poems when I was around fourteen years old and it took over my life. I’d sit in school and daydream, I’d stare out the window, or I’d write a poem. In the evenings, when I was avoiding doing school homework, I wrote poems. I was the editor of my high school’s literary magazine, and I published some of my own poems in it, but anonymously. Two excellent English literature teachers at Monklands were Mr. Boswell and Mrs. Montin, both encouraged my interest in English literature. I remember attending summer school at nearby Montreal West High School for a failed math course—I sat at the back of the class and wrote poems—of course, I failed the course and never took math again, but I’m still writing poems.

4. What is your working definition of a poem?

Poetry is largely metaphor, but it is also concise language, language imbued with some quality of music, and language that communicates an emotion. Poetry usually builds on the work of earlier poets, so there is a tradition or a lineage to the kind of poetry one is writing. Poetry is much more open-ended today than ever before: we have concrete and visual poems, sound and performance poetry, poetry that is computer generated, and so on. The study of ethnopoetics has embraced poetry by indigenous people from around the world, this literature was formerly of interest mainly to anthropologists. Diversity has increased the definition of poetry and the varied field of poetic expression open to poets today. In general, what I perceive as a “real” poem makes me want to write poetry. It inspires me to write. However, no single definition of poetry will suit everybody.

5. Do you have a writing ritual? If so, provide details.

By ‘ritual’ I guess you mean some repetitive, perhaps obsessive and compulsive, task that has to be done before one can write. The tennis great, Rafael Nadal, has his obsessive rituals, for instance listening to a certain piece of music and having several showers before entering the court, lining up bottles of water beside where he’s sitting during a tennis match, and so on. I don’t have any ‘rituals’ like this, I just do the writing.

6. What is your approach to writing of poems: inspiration driven, structural, social, thematic, other?

CZ, who is a poet and editor as well as my wife, often gives me titles for poems and I can usually direct my inspiration into whatever the title suggests to me; at other times, I’ll sit and write and later, with a lot of editing, I’ll find the poem hiding in what I’ve written. When I’m writing, I don’t know in advance where the writing will take me. I think of this writing as improvisation, on a title or a theme, on what these suggest to me, or on an emotion. Of course, the process of writing poetry is a lot more complicated than this but it gives a general idea of my approach to writing.

7. Do you think that being a minority in Quebec (i.e. English-speaking) affects your writing? If so, how?

This question raises a lot of contentious issues. I feel that over the last thirty or forty years Quebec politics—the question of Quebec’s separation from Canada and the language issue in Quebec—has soured and made unpleasant the experience of living here for many people, including myself, in the English-speaking community. This situation is complicated and affects one’s daily life although I doubt it is a subject for much poetry written here.

8. Do you think that writing in English in Quebec is a political act? Why or why not?

English is one of the most used, most spoken, languages in the world, so when English is your mother tongue you don’t really think too much about writing in any other language or that writing in English is a political act. Politics—government and how best to govern the country—have always been of vital interest to me, as a social democrat and as someone who believes in the western liberal tradition. Politics are defined by where one lives and when; poetry is not defined by time and place. My calling in life has been to poetry and not to politics.

9. Why do you write?

Writing, being creative, is a celebration and an act of affirmation. For me, this is an important aspect of writing poetry. We need to embrace life and not accept an attitude of denial that is so easy to fall into. The very act of writing affirms life, even if the content of the writing is negative or questions ultimate values. Some of my work deals with death, regret, and grief, all negative subjects; but for me, writing the poems I have written has also been to rise above personal experiences. To write poetry is to affirm being alive.

10 Who is your audience?

While a poet’s first reader is himself, there are also many others who read poetry. I give numerous readings in Montreal, and there are always people who speak to me after the reading. They thank me for a particular poem, they have questions or express interest in something mentioned in the poetry. I’ve read my work to audiences across Canada and in different parts of the United States. There are many people who are readers of poetry, although maybe not as many as those who read detective novels!

When CZ and I were in New York City last year we read at Haven Art Gallery in the South Bronx. We spent a delightful hot summer evening meeting both audience members and other poets who read at that event. It was really quite exhilarating to meet so many people who value both poetry and poets. Later, we visited the New York Public Library where we found copies of all our books, available to readers there. Our books are also in major libraries across Canada. So, you see, the audience is there and it is a large one.

I was one of the eighteen poets who gave readings for the Montreal Gazette’s online poetry reading series this summer, 2009; each poet read only one poem. What a varied group of poets! This type of experience was impossible before the Internet; now, anywhere in the world, people can see Montreal poets read their work. With the Internet we have an international audience that is beyond anything possible in the past. My website, www.stephenmorrissey.ca, also includes some of my poems, and it has at least sixty new visitors at the site every day from all parts of the world; again, this kind of exposure for poetry was unheard of just a few years ago.

CZ and I co-founded www.coraclepress.com and publish online poetry chapbooks and, more recently, print medium books. The online chapbooks reach an enormous audience in all parts of the world. The opportunities for publishing have increased with the many literary sites and magazines. In terms of audience, I don’t think there’s a better time to be a poet than now. In the future readers will be able to purchase books, printed on demand; we are increasingly moving away from print medium to digital. I welcome these changes.

11. Do you think there is an audience, outside of friends or other poets, for poetry?

Audience is there, at readings, online, or listening to literary programmes on the radio. I’ve read my work before audiences at conferences, universities, high schools and grade schools, coffee houses, church basements, and other places. There is also the more personal experience we have of audience, one day you meet someone reading a book of poetry, and they’re the last person you would expect to read poetry but there they are, carrying a book of poetry and reading it on the bus, or where they work. One of the best public reading experiences I’ve had was at the N.D.G. Food Depot over the course of several years. Here was a group of people who needed to visit the food bank to make ends meet. These audiences applauded after each poem, and were genuinely enthusiastic and appreciative of my reading. Many came up and talked to me after the readings. I was deeply touched by their welcoming and positive response.

12. Does your day job impact on your writing? How?

Writing requires time to write. A day job that gives you time to be by yourself is what poets need. If your day job takes up too much time, writing will be impossible. Poets also need time to revise their work, read what other poets or writers have written, and time to daydream. It is very difficult to write poetry if your day job demands too much of your time, your thinking, your being. I have been blessed by having a college teaching position that has allowed me to enjoy the work I have done to make money, but also the time that is needed to do my writing.

13. How many drafts (beer too) do you usually go through before you are satisfied/finished with a poem?

As many drafts as it takes, but seemingly more drafts as I get older. A poem might take fifty drafts, or be publishable with the first or second draft, although, for me, this seldom happens. The editing process is laborious and takes up a lot of time. When CZ edits a poem for me it goes a lot faster, she is not only a brilliant poet but has many years of experience editing poetry, and this is a gift that is not found in many editors.

14. Do you write with the intention of “growing a manuscript” or do you work on individual poems that are later collected into a book?

My ambition has always been to write a thematically cohesive book. I remember, in high school, running home at lunch time and listening to the Beatles’ “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” I believe this is one of the first concept or thematic albums. Then, there was also Frank Zappas’s parody of the Beatles’ album, and that was also fun. It was from the Beatles that I had the idea of a thematic book of poems, and I’ve followed this ever since. My new book, Girouard Avenue, is the most cohesive and thematic of all of the books I’ve written. It took many years to write Girouard Avenue, I must have started the writing in 1995, and then I’ve waited years to publish the book, my first since 1998. Girouard Avenue begins with a prologue, “Holy Well,” a memory of Ireland from where my family originated, but it is a mythical Ireland, a place of the unconscious mind, and then the poem also reflects on where we are today, in Montreal. The unconscious has always been important to my work, as it must be to any poet, for where do the poems come from but the unconscious, that place of dreams, mythology, and psychological and spiritual depth.

There are four long poems in Girouard Avenue, the first two are poems of place, of different homes where we lived in Montreal. The first of these is “Girouard Avenue Flat” which celebrates my grandmother and includes family history. She lived for over forty years at 2226 Girouard Avenue, renting a large flat below Sherbrooke Street West in Montreal. This home was busy with the daily life of a large family, which included seven children. Many played musical instruments. Other family members also lived there, due to illness or old age. Even my parents and my brother and I lived on Girouard Avenue in the early 1950s, with my grandmother, my Aunt Mable, and my great aunt Essie, because of my father’s heart condition. Before that we had lived a few blocks away on Avonmore. This was my parents’ first home after they married in 1940, but a small 3 ½ room apartment wasn’t a good environment for a family of four people when one of them is seriously ill. After the war it was difficult to find a larger apartment to rent, so off we went to Girouard. By 1969, after my grandmother died, there was just my grandmother’s two very elderly sisters left living there and I talk about visiting them with my brother at Christmas.

The next poem is “Hoolahan’s Flat, Oxford Avenue,” where we moved in 1954, after living at my grandmother’s for the previous two years. “Hoolahan’s Flat, Oxford Avenue” is a poem of the 1950s, of television, and family. In this poem I purposely avoided being overly confessional or emotional in favour of a kind of reporting on the times in which I lived, what they were like, in a fairly matter-of-fact way. I mention my first friend, Audrey Keyes, the girl next door, and over forty years later Audrey saw the poem online and contacted me, and we’ve become friends again, as though no time has intervened.

These first two poems in the book are of places where I lived in Montreal, but they are also significant for other reasons. More happened in these two flats than just daily life. These homes were foundational to the development of who I am as a poet and as a person. Even as a child I felt there was a bravery and heroism to everyday life as it is lived by everyday people. There is a courage in average people that has always interested me. I’ve loved stories of family, of who did what and when. These family stories are framed by history. These accounts have an aura of historical reality; my poems about family are also poems of spirit, of courage, of dedication to family and everyone working hard. This is what I want remembered, so that these people aren’t forgotten, so that the ancestors are suitably remembered.

“November” is the third long poem in Girouard Avenue. The month of November is the time when I have always been closest to the unconscious mind, to dreams, to Spirit, to what the spirits say to me. The days are growing shorter, we are moving relentlessly into winter, and the fabric between our material world and the other world is at its thinnest. Now I return to my father departing for Boston in 1956, where he died a few weeks later; but I also reflect on the importance of the railroad in Canada. Many members of my family worked for the Canadian Pacific Railroad. The railway was an important form of transportation in the past. In this poem there is the juxtaposition of the personal with the impersonal, but always memory of the people I am descended from and who I honour. But a poet is more than this: a poet affirms life and writes from a vision that reminds the reader there is more to life than mundane activity, there is epiphany, spirituality, aesthetics, and dignity even in the most humble people.

The final poem in the book is “The Rock, Or a Short History of the Irish in Montreal” and uses my own family’s history in Montreal, from when they arrived here around 1844, to recall something of the history of the Irish in Montreal. The Irish were an enormous immigrant population here; people who mostly arrived with nothing, which is also the story of the Irish in other North American cities. Within several generations these Irish immigrants rose to become doctors and lawyers, politicians and leaders in government. The Irish have always believed in education and fighting to survive.

There is the Black Rock, a memorial to the Irish who arrived in Montreal in 1847 from famine-ridden Ireland, only to die in fever sheds located near present-day Victoria Bridge. Here you can see the heroism I am referring to. Families came all this way from Ireland, so hopeful, so desirous of a new life, and then five thousand of them perished soon after arriving. It’s a tragic story but at least they opted for survival and a new life, rather than give up and die in Ireland.

Having said this, perhaps there’s a balancing of tragedy and bravery that I find compelling. It is also my own Irish sensibility that causes me to perceive tragedy and melancholy in what I see around me, in the stories and lives of people. Even my father’s story is a combination of bravery and tragedy: he was a man of such intelligence that he rose from the working class to quite a prestigious executive position in the C.P.R., but he had rheumatic fever when he was a child and this eventually caused medical problems, scarring of his heart, that caused his early death. He didn’t give up, he lived as long as he could, he had a family, he did his best despite knowing that his life would not last as long as other people’s. Had my father lived for just another six months medical advances were achieved that could have extended his life for many more years. But that was not to be. His death when I was only six years old changed my life, and perhaps it made a poet out of me.

The last poem, the epilogue, is “The Colours of the Irish Flag,” which celebrates marriage, family, and love. But it is also a poem about being strong, not being defeated without a fight for one’s survival, or the survival of what one believes in. You don’t just roll over and give up, you fight, you struggle, you go the distance, you don’t be a coward, you be a man or a woman. We’ll have no cowards here. You can see that I feel very strongly about all of this.

15. What is the toughest part of writing for you?

Because every poet is different, what is difficult for one poet may be simple, or come easily, to another. I’m sorry I can’t be more specific. Writing is a lot of work and requires dedicating your life to this art. What is tough changes with time. Consider poetry all hard work; it’s all tough.

16. What is your idea of a muse?

A muse is what Sharon Stone portrays in the film The Muse. A muse brings a man to life, and my life since meeting CZ has been transformed by her. The feminine animates the empty or damaged shell that is the condition of some men or women. A muse inspires creativity. There is always a price to be paid for having a muse; it’s not something to be trivialized, the muse needs to receive presents for her work, and not cheap baubles, as Sharon Stone‘s character made clear in this film. There is no free ride in this life. Creativity is a lot of work with a few moments of rest, but worth every minute of the journey. You can always rest when you’re dead, because living is to embrace life and accept the challenges of inspiration more fully, more consciously. The idea of a muse is no simple topic, and you don’t have to be a poet to be moved by a muse.

17. Do you have a favourite time and place to write?

I’ll write just about anywhere and at any time. I’ve written poems during classes when I was a student and I’ve written while classes of my students are writing a test when I was the teacher. I’ve written during other people’s readings and while lying in bed with the only light being from a flashlight. I’ve written sitting on a lawn chair balanced on a rock in the middle of a river. I’ve written sitting on a beach in both Vancouver and Mexico. I’ve written during snowstorms and heat waves. I’ve written in hospital cafeterias and waiting rooms. I’ve gotten up in the middle of the night and written down a poem that came to me in my sleep, or that I was writing in my mind while still awake in the dark. I’ve spent innumerable hours sitting at desks writing poems. This isn’t just my experience but probably the experience of many poets.

18. Do you like to travel? Is travel important to your writing? Explain.

I can’t say that I like to travel, although I’ve done my fair share of traveling. I enjoy travel on business, for a conference, or to visit relatives or friends, but being a tourist for its own sake doesn’t interest me. I agree with Thoreau’s sentiment when he said, “I am well traveled in Concord.”

19. Do you have a favourite Quebec poet? If yes who and why?

My favourite Quebec poet is Louis Dudek. I don’t think his work is dated at all, it’s contemporary and significant. One day more people will hopefully realize how accomplished and important a poet Dudek really was. Doug Jones is a gifted poet and John Glassco, who is mostly known for his memoir, is also a very good poet. Artie Gold is a terrific poet who was very talented and creative. Of course, I always enjoy reading what friends are writing, such as Carolyn Zonailo, Sharon H. Nelson, Carolyn-Marie Souaid, and others who are my contemporaries. For many years I’ve liked Deborah Eibel’s original voice in poetry. Ian Ferrier is a wonderful spoken-word poet. I meet and hear interesting new Montreal poets, talented younger voices, at readings that I give or attend. It is with great sadness that Montreal’s poetry community lost the poet and painter Sonja Skarstedt who died this summer, 2009. Emile Nelligan, St-Denys Garneau, and Anne Hébert are three poets I teach in translation, and I continue to enjoy their work very much. All of these poets stand out for me as exceptional.

20. Do you write about Quebec? If so, how and why? If not, why not?

Some poets write from a specific place that they are identified with, but they always transform the specific into the universal. So, Charles Olson’s Glouester and William Carlos William’s Paterson are places that are identified with these poets but are also places that have been transformed into an archetypal geography that represents the human condition in general. That’s why I named my selected poems Mapping the Soul: Selected Poems 1978-1998 (Muses Company, Winnipeg, 1998). In my writing I am not only interested in a geographical location—for instance, Montreal—but in the manifestation of the soul in this place, in the expression of the landscape of the unconscious mind, this is what interests me. I won’t always write about Montreal, but in the writing I have done that refers to this city, and the work I am doing now, I am attempting to transform the city into something more than a specific place, but always retaining the specificity of the place.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)