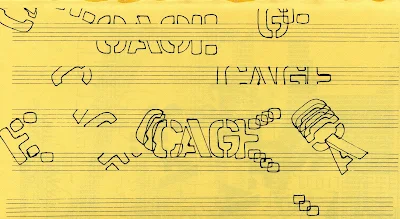

Here are two boxes of Krishnamurti books, destroyed when our basement flooded.

|

When our basement flooded two years ago I lost books, literary papers, archives, old family photographs, manuscripts, and old diaries. Losing these things was strangely liberating, I didn't really care as much as I thought I would. I had already begun discarding books; years before the flood I began downsizing my library; I kept poetry and books on poetics, biographies of poets, books on poets’ work, books of interviews with poets, and some other books that still meant something to me. But fiction was easy to discard, except for a few novels--Moby Dick, The Great Gatsby, novels by Margaret Laurence, and other Canadian novelists--most of the rest were discarded.

Years ago I read all of Henry Miller's books, some were purchased second hand, some new, some remaindered, and some from antiquarian book stores. I read books that Miller recommended, for instance, the diaries and novels of Anais Nin and I heard her speak at Sir George Williams University; I read Blaise Cendrar and other writers that Miller knew. Read Henry Miller's The Books in My Life (1952); I am pretty sure that I discovered J. Krishnamurti because of Miller's essay on him in this book. I remember late one day, taking a city bus home, and meeting Louis Dudek on the same bus; he had planned to publish something by Henry Miller but decided against it; he writes, somewhere, that the big influence on his writing was Matthew Arnold and Henry Miller. He liked Miller’s conversational style of writing and that Miller was intelligent but not academic.

Also, I must have read all of the novels of Jack Kerouac, and then I moved on to other Beat writers, Corso, Burroughs, Michael McClure, Ferlinghetti, and Diane di Prima. It used to be that when I would read someone whose books I liked I read all of their work, their novels, poems, essays, letters, books on their writing, and biographies. And I’ll read the books they recommend or books that influenced them.

I began reading Jack Kerouac in the fall of 1969, around the time I heard Allen Ginsberg read his poems at Sir George Williams University where I was a student; by then, Kerouac had fallen into obscurity, he drank his way into oblivion, and then he died; by then the public had moved on from the Beatniks to the Hippies and left Kerouac behind. Back then, in 1969, I found it difficult to find Kerouac's books; today, they're in the remaining bookstores that we have. But now I have no real interest in Kerouac or Allen Ginsberg. As bpNichol said to me, when he read his work at the college where I was teaching, Kerouac is for when you are young, when you get older you want something more substantial. I'm no longer interested in reading Kerouac's novels but I kept his poetry, I still like Kerouac's poetry.

I remember the evening of 21 October 1969, a dark and rainy evening, I was downtown on McKay Street when I heard that Kerouac had died. But death was good for his reputation as a writer, over the following years and decades his popularity has grown and his unpublished manuscripts have been published; books on Kerouac, biographies and memoirs, have also been published.

Back in the late 1960s there were still people around who had known Kerouac from his visits to Montreal. A professor and friend, it was Scotty Gardiner at SGWU, told me that he expected Kerouac to come for supper at a friend's home but Kerouac never arrived. It was the usual story of a drunk Jack Kerouac disappointing people and not caring, he could be belligerent and argumentative when drunk. Ginsberg also read in Montreal, in November 1969, and from where I was sitting I could see George Bowering in the first row with Peter Orlovsky. The years passed and Ginsberg returned to read in Montreal (I can't find documentation for this visit) but Ginsberg's readings were no longer important cultural events, it was golden oldies, and people demonstrated against Ginsberg's advocacy for adult men having sex with young boys. Ginsberg discredited himself advocating for this issue, he was not ahead of his time, he was out of touch with society, its norms, and values. Here is something ironic: a few days ago I read that when Ginsberg was young, he lived for a while with William Burroughs, and when he moved out he complained to Burroughs that he didn't want to have sex with some old man... Actually, Ginsberg said a lot worse about Burroughs' private anatomy than I will repeat. Ken Norris writes in a poem that, when he was young, poets were our heroes, and they were. A friend, Trevor Carolan, wrote on Ginsberg in Giving Up Poetry: With Allen Ginsberg At Hollyhock (Banff Centre Press, 2001). Ginsberg, like Kerouac, is a writer of one's youth, not one’s older years.

Our flooded basement:

|

| Flooded basement, July 2023 |

.jpg)