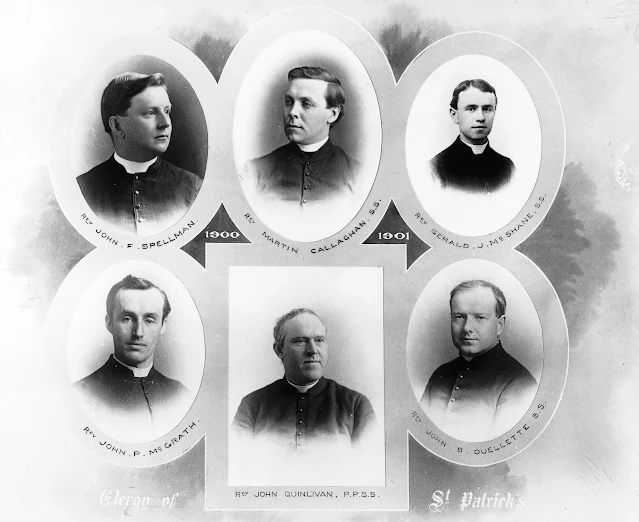

When I was growing up I often heard about the three Callaghan priests, Frs. Martin, James, and Luke. The oldest priest was known familiarly as Fr. Martin, he was the first Montreal-born pastor at St. Patrick's Basilica; when he died he was buried in a plain wooden casket and, as his funeral cortege moved through the streets, people bowed their heads and acknowledged that he was an exceptional and humble man of God; they all loved Fr. Martin. Fr. James, the second born, was less known; the youngest, Fr. Luke Callaghan, was prominent but not as beloved as Fr. Martin.

The Callaghans were proud of all of their children. John Callaghan, their father, was involved in religious organizations in Montreal and, coincidentally, he was a longtime friend of my great great grandfather, Laurence Morrissey, a relationship that predates the marriage of his daughter to Laurence's son, Thomas. The Sulpician order educated these three young men and they each became prominent figures in the Montreal community. Born into the working class their intelligence was recognized by the Church and they were given every opportunity to make something of themselves; they were given the greatest gift, an education.

There is a saying, that one pays something forward (defined as "when someone does something for you, instead of paying that person back directly, you pass it on to another person instead.") Back in the 1920s and 1930s, and before, some members of the Irish Catholic community in Montreal wanted to build a hospital, and they did, it is St. Mary's Hospital which is also a McGill University teaching hospital. It was Fr. Luke Callaghan who saved the hospital when it was in jeopardy of being cancelled; he paid forward the good fortune that he had received from others.

|

| Father Luke Callaghan |

..jpg) |

A Notman photograph of St. Michael's Church, 1934; Fr. Luke Callaghan

was the pastor here and he helped build the church.

|

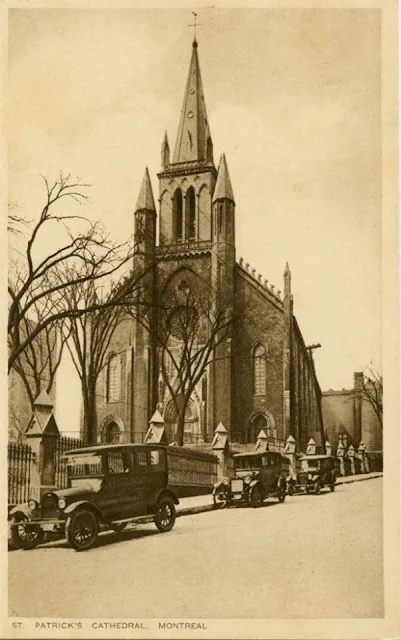

The mission of founding a hospital originated with Sister Helen Morrissey (no relation) in 1908; she was born in Pickering, Ontario, and she was joined in this work of founding a hospital by Dr. Donald Hingston, an eminent Montreal surgeon and a member of an eminent Montreal family, his father had been a surgeon and mayor of Montreal. The first location of St. Mary's Hospital, chosen by Mother Morrissey, was Shaugnessy House, on then Dorchester Blvd West, and it opened on 21 October 1924; it is now the location of an architectural centre and museum.

Shaugnessy House was soon recognized as being too small to serve its purpose and work began raising funds for a new much larger building. But the main hurdle was Mother Morrissey, she had her own vision of the new hospital, and that vision was that it would be under her control. She was also convinced of her own correctness, she was domineering, intelligent, articulate, and formidable. She was a literate person, she had written a book on Ethan Allen, and she knew what kind of hospital she wanted; soon, the business men fled saying Mother Morrissey was unworkable with. The men could do nothing with Mother Morrissey, she would not budge from her belief in what she wanted and her moral authority in getting it.

|

The original St. Mary's Hospital located at Shaugnessy House

|

.JPG) |

| St. Mary's Hospital in 2014 |

It seems that the men, prominent business men and politicians, cowered in the presence of Mother Morrissey, or they threw up their hands and were prepared to let the whole project become history. Thomas Morrissey was married to Mary Callaghan, a sister of the three Callaghan priests, and when Thomas died in 1916 Mother Morrissey visited the family in their working class home. Also present were Mary Callaghan's brothers, the priests. So, when the hospital project went off the rails due to Mother Morrissey, who did they call? They called the only man who had the authority and connections to do an end-around Mother Morrissey, they called Father Luke Callaghan, pastor of, at the time, the largest Irish congregation in Montreal, St. Michael's Church on St. Viateur Street in Mile End. Perhaps Fr. Luke had a chat with Mother Morrissey, he had the diplomacy to deal with all sorts of people and to get them onboard; he had seen through the building of St. Michael's church, a church that is architecturally unique in the city. Having lost her position of authority in the hospital project, Mother Morrissey seems to have disappeared from her involvement with the hospital. Soon, a million dollars was raised for the construction of a new hospital. The new hospital, located on Lacombe Avenue near Cote des Neiges Road, opened in 1934, where it is still located.

Canon Luke Callahan was named by Dr. Hingston as the

man who, through his intervention with the Archbishop during

the 1929 closure, saved the hospital. Father Callahan had

persuaded the Bishop to sanction the removal of Rev. Mother

Morrissey and bring in the Grey Nuns. Many of the Irish clergy

had been strongly in favour of turning over the hospital to Rev.

Mother Morrissey or another religious nursing order. The

community in general was dissatisfied with the doctor-dominated board and it was during this state of general discontent,

that a new board of prominent businessmen and politicians was

established prior to the first major successful drive in July 1931.

I tell this story because some years ago someone very close to me was very ill, at one point she almost died while in hospital, but doctors and nurses rushed to her bedside and by the next morning she was still alive, but barely. Every year I expected it to be her last but it is now eight years later and each year is a blessing, it is a gift and to whom do I owe this gift? To the doctors, nurses, administrators, and staff at St. Mary's Hospital. God bless them all! And to whom do I owe this hospital? To Mother Helen Morrissey, Dr. Donald Hingston, and Fr. Luke Callaghan who helped keep the hospital project alive; he paid it forward and I, his great, great nephew, am one of the many recipients of his gift. Then, in June 2021, I had cancer, it required surgery; I was referred to the chief surgeon at St. Mary's and, within a few weeks, I was operated on and here I am, writing this and once again thankful to the doctors and nurses at St. Mary's Hospital and Fr. Luke for saving it from the misguided control of Mother Morrissey. By the way, I have no special privilege at the hospital; everyone is treated equally with dignity and care.

And this is what "paying it forward" looks like from someone who has received the generous gift of those who paid it forward. I hope everyone can be generous and give something to a reputable charity like the St. Mary's Hospital Foundation. Fr. Luke, when he helped save St. Mary's Hospital, had no idea that it was descendants of his own family that would be saved by his intervention with Mother Morrissey.

Merry Christmas to you all!

Note: Sister Helen Morrissey's book, Ethan Allan's Daughter, was published in Montreal in 1940.

%2023May1942%20p16%20%5BNewspapers-Com%5D.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

..jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)