Wednesday, October 22, 2025

Lane behind 2226 Girouard Avenue, 22 October 2009

Monday, December 23, 2024

St. Mary’s Hospital, Paying it Forward

.JPG) |

| St. Mary's Hospital, 20 August 2014 |

Walking down the hall at St. Mary’s Hospital, I said a silent thank you to Fr. Luke Callaghan for saving the hospital. Back in the 1930s Dr. William Hingston, who founded the hospital, asked Fr. Luke for help dealing with Sr. Helen Morrissey (no relation to me), the nun who had initiated the idea of a hospital for Montreal’s Roman Catholic population; however, Sr. Helen had her own rigid ideas of how the new hospital should be run, and she proved an obstreperous and formidable opponent as she alienated the all-male board organizing the new hospital. She almost derailed the hospital before it had even opened. As a last resort, and exasperated with Sr. Helen, Dr. Hingston called in Fr. Luke, who was the pastor at St. Michael’s Church in Mile End, to see what he could do about the situation. It was because of Fr. Luke’s intervention that fund raising and building the new hospital could proceed. Soon, the new St. Mary’s Hospital opened and it has been serving Montrealers of all faiths ever since.

It occurs to me that at this time of the year, a time for giving and thanks, we might remember those people from the past who made our present lives possible. Fr. Luke Callaghan, who is also my great great uncle, helped pay forward the gift of St. Mary’s Hospital. This hospital saved my wife’s life ten years ago; my two grandsons were born here; and the doctors, nurses, and technicians at St, Mary's gave me truly exceptional care just three years ago when I was diagnosed with cancer, they saved my life.

I would be a terrible ingrate if I did not contribute to St. Mary’s Hospital Foundation. I think of Fr. Luke Callaghan and the words of Dr. William Hingston, “In my opinion, Luke Callaghan saved St. Mary's.” Of course, Fr. Luke probably never heard of the phrase “paying it forward” and he had no idea that his intervention to save the hospital would also help his family’s descendants ninety years later, but that’s exactly what he did; we, too, can pay forward something of what we have received. Be generous, be giving, and pay forward what we have been given for future generations.

Notes: Quotation from Dr. Hingston is from Allan Hustak's At the Heart of St. Mary's, A history of Montreal's St. Mary's Hospital Center, Vehicule Press, 2014.

I also recommend Dr. J.J. Dinan's St. Mary's Hospital, The Early Years, Optimum Publishing International, Montreal and Toronto, 1987.

Monday, September 25, 2023

Loyola College, Montreal

Not far from where I live is the former Loyola College (on Sherbrooke Street West near West Broadway); it is now, as of 1974, a campus of Concordia University. Concordia University was created by the amalgamation of Sir George Williams University, which was associated with the YMCA, and Loyola College, which was a Roman Catholic institution. Loyola College is one more institution built by Montreal's Irish community, as is St. Mary's Hospital. The college seems to have retained its heritage and religious foundation, as far as this is possible in today's secular world. Hingston Residence is on the campus, William Hingston being an important historical figure in Montreal. There is a free shuttle bus service for students that takes you to the downtown campus in a half hour, or less depending on traffic. Vanier Library is found here as are newer science buildings.

Photographs taken the morning of 9 September 2023.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

Father James Callaghan

|

| Photographs of Fr. James Callaghan, Notman photograph, archived at McCord Museum, Montreal |

Father James Callaghan

Father Martin's next younger brother is Father James Callaghan. After completing his grade school studies with the Freres des Ecoles chretiennes, James Callaghan (born Montreal, 18 October 1850) studied classics at the College de Montreal (1864-1872). He also studied at the Grand Seminaire de Montreal from 1872-1875, and he completed his studies at the Seminaire Saint-Sulpice de Paris in 1875-1876. After Father James entered the Sulpician Order all of his studies for the priesthood were conducted in France. He became officially a member of the Sulpician Order when he was ordained a priest on 26 May 1877 in Paris. Returning to Montreal, he was the vicar at St. Ann's Church in Griffintown from 1877-1880; this church was demolished in the 1970s but in the late 1990s the foundation was excavated by the City of Montreal and the triangular lot on which the church was located was made into Griffintown-St. Ann's Park. While at St. Ann's Father James lived in the church presbytery at 32 Basin Street in Griffintown. Father James also worked as a professor of English at the College de Montreal (1880-1881). He was a vicar at St. Patrick's (1881-1896) during which time he and his brother Father Martin lived at 95 St. Alexander Street, later they moved to 92 St. Alexander in 1887; 770 Dorchester Street in 1891.

Father James was professor of ecclesiastical studies at the Grand Seminary of Baltimore, Maryland (1896-1897), and in his last years he served as the chaplain at Hotel Dieu Hospital and the Royal Victoria Hospital (1897-1900). He died of kidney failure at Hotel-Dieu Hospital on 7 February 1901, age 51 years. He is described in a church biography as having a beautiful soul, as being innocent and open to other people, full of spontaneity, and as a man who is not guarded or calculating. -o- Here is the official memorial for Fr. James Callaghan from the Sulpician Order: Callaghan, Father James Date of Death: 1901, February

6 Date of

Birth: 1850, October 18 Aix, France March 19, 1901 Fathers and Very Dear in Our Lord: No Memorial Card is Available The huge crowd that Montreal saw gather for the funeral of Father James Callaghan said quite loudly by its presence what affection and what recognition Irish Catholics know how to pay to their priests. It served also as a eulogy on the priestly virtues and sympathetic qualities which our dear departed one had displayed in his ministry, especially during the fifteen years from 1881 to 1896 when he exercised that ministry in the great parish of St. Patrick’s. Father James Callaghan was a child of that parish. He was born there on October 18, 1850, of a faith-filled family which has given three sons to the Church. Even as early as his grade school years with the Christian Brothers he was known for the vivacity of his spirit and for a sunny disposition which never stopped being an important trait of his character. All his life, moreover, exhibited the evidence of a beautiful mind, innocent and uncontaminated, full of spontaneity and of lively impulses which he acted on after thinking them over or weighing the consequences. At the age of fifteen he went to join his brother Martin at the college of Montreal; Martin had preceded him there by three years. There he became a member of a class which has counted twenty-three priests. Amidst so many pious fellow students, the good James distinguished himself less by application to and intensity of work than by the ease with which he did it through a quick and unlabored intelligence, and especially by a character of gold. When he finished his classical course, he unhesitatingly entered the Grand Seminary where the study of sacred sciences roused – even to the point of enthusiasm – that fire of soul which nature and faith together built in him. Ordained subdeacon on May 22, 1875, at the same time as his brother Martin was finishing his year of Solitude, Father James Callaghan soon felt himself attracted to follow his eldest brother to that very place. First, he came with two other confreres to spend a year at the seminary in Paris, entered the Solitude in October 1876, and was ordained priest there on the following May 26th. Some weeks later he brought back to Montreal the first fruits of his priesthood. The first field assigned to his zeal was the Irish parish of St. Anne, still staffed at that time by the priests of St. ___. Among all the works of the holy ministry those on which the young priest especially spent himself with ardor were preaching (for which he was well endowed) and the needs of the young people, whose hearts he very well knew how to win by the liveliness of his faith and his sympathy for their years. After three years of this ministry there was a development which occasioned the trying out of Father James Callaghan as a teacher. St. Anne’s parish and the French parish, St. Joseph’s, were given over by the seminary to diocesan administration. In the new appointments of those who were formerly St. Anne’s priests, Father James was sent to the college as teacher of English. He did good work there and was popular with the youth; but he was subject to distractions and promptings which, considering his duties, were not helpful to the general good order – forgetting sometimes and at other times mistaking the hours of his classes; letting himself, while conducting class, indulge in witty comments on the dry exercises of the day’s lessons, comments which went too far. From the beginning of the school year in 1881, he was given his position of choice, parochial ministry, this time in the mother parish, St. Patrick’s, under the firm and experienced hand of the revered Father Dowd, in whom affection and authority combined to draw out the best of the talents of the young priest. Of this fifteen years of his ministry at St. Patrick’s the Semaine Religieuse of Montreal has said: “To speak of his inexhaustible charity to the poor to whom he was long, by appointment, the dispenser; of his zeal for the instruction and the return to the faith of our separated brothers, of whom he converted a great number; of his dedication to the young, whose works and meetings he oversaw; of the reverence that he always displayed for God’s Word, which he proclaimed with dignity and often with flair; of the retreats without number which he gave to the school children; of the kindness with which at all times he made himself available to everyone – would be superfluous after the magnificent funeral which piety and recognition have given him. At this turnout, how could anyone avoid thinking of the words of the great apostle speaking to the Corinthians – Epistola nostra vos estis quae scitur et legitur ab omnibus homnibus?” (You are our letter, known and read by all?) Those who knew Father Callaghan most intimately have commented on his lively faith, his attachment to St. Sulpice, his obedience to his superiors; and they add that these last two traits especially showed themselves in the last years of his life. I myself, five years ago, experienced that disposition of obedience when I had to ask of Father James Callaghan a sacrifice which could but be keenly felt by him. It was the matter of his leaving his dear St. Patrick’s to go to help out temporarily at the Baltimore seminary, where there was need in Philosophy of a Professor of Holy Scripture and Church History. With no hesitation he assented to my request; went off to Baltimore (as he did everywhere he was assigned), as a good confrere; did his best at his assigned tasks. And when he returned to Montreal the following year, he let himself be placed with the same meekness where his work would be most useful, that is to say, at the Hotel Dieu as chaplain of the sick at that hospital and at the neighboring English hospital. It was in that dedicated ministry (to which he had already been introduced during his time at St. Patrick’s) that he spent the last three years of his life. Without doubt, God had arranged things for him to prepare him for that last journey on which he daily had to act as guide to many poor souls. Many a time during these years he said to his superior: “Don’t be afraid to assign me as you will; I want only to do what you want.” “Some seem to think I want to go back to St. Patrick’s,” he said during the last vacation period. “Leave me at the Hotel Dieu, call me to Notre Dame. I will be happy anywhere you decide I should be.” At that time, he still seemed full of vigor. A little later it was perceived that he was suffering from a severe organic illness, and Father Colin suggested to him to go away for awhile for his health’s sake. The sick man knew that an American bishop who had been his fellow student would welcome him with open arms. But for him that was all the more reason to say: “Please don’t send me there. He would want to keep me with him, and for nothing in the world would I want to leave St. Sulpice.” The kidney disease afflicting him rapidly became fatal. When his stomach and heart became affected, Father Callaghan was visibly wasting away, and our doctor lost the hope that he had at first entertained. Two other doctors, called in for consultation, held the same opinion. The dear patient, however, was not aware of his danger. “I resolved,” wrote Father Colin, “to administer [Extreme Unction] to him while he had still had all his faculties. It was at that time I saw, as never before, all there was of grace and virtue in that beautiful soul reveal itself. On Saturday morning, January 12th, I suggested to him that he prepare himself for his end. ‘First of all,’ he told me, with a pleasant and smiling air, ‘I want to save my soul and give myself to God. Tell me what you want.’ After his confession, which he made with all his heart, he said to me, ‘Take me along with you. I want to be in the seminary infirmary in the midst of my confreres whom I love so much and be near you. It is there I wish to get ready to go, if God calls me.’ I decided nevertheless that it would be wisest for him to stay at the Hotel Dieu, and I told him I would come back between four and five o’ clock. In that visit, I still did not make up my mind to administer [Extreme Unction] to him; but towards eight o’ clock the sisters, quite upset, called me, and I simply told him that it would be more prudent to receive the last sacraments. ‘God wills it, and so do you,’ he told me, ‘so I do too.’ The family, several confreres, several religious, gathered round. He reacted to everything with a kind of happy enthusiasm, with the result that the ceremony was most edifying and touching. The next day, a noticeable improvement was evident, and the doctor once again took hope of keeping him for a while longer; but the improvement was of short duration. “On Wednesday, February 6th, the dear patient, being very ill but still displaying presence of mind, I had him celebrate his [silver] jubilee. The simplicity of his abandonment to God struck me once again as wonderful. The next day he felt better and expressed his joy for the grace received the previous day. At four in the afternoon he spoke of it complacently to Father Quinlivan, who had come to see him. At half past five, his brother Luke, while helping him from his armchair, asked him, ‘Are you all right?’ ‘Yes, I’m all right,’ James answered him. And while saying this, he died without agony. On seeing his head drop, his brother had the presence of mind to give him a final absolution.” When the body was laid out in a parlor of the Hotel Dieu, several thousand visitors came the following days to pray over him. Two days later, on Thursday, February 7th, a first service was sung at the chapel of the house by Bishop Racicot. On Sunday, at five in the evening, the Reverend Superior of Montreal, with an immense crowd on hand, presided at the moving of the body to Notre Dame church, where soon after the Office of the Dead was chanted. On Monday morning at the funeral Mass, sung by Father Leclair in the presence of the many who attended, His Grace, the Archbishop of Montreal, deigned to give the absolution. Later, the burial at the Mountain was conducted by Bishop Emard of Valleyfield, former fellow student of the deceased. Finally, on Wednesday, February 13th, a third Solemn Mass was celebrated at St. Patrick’s by the pastor, and parishioners again came in great numbers to pray for their former assistant and to express their condolences to the worthy family. Father James Callaghan’s old father – who survived him – like us, could not keep from finding such a death very sad and very premature. But with the dear deceased (when his situation was made clear to him), ‘we must all say: “God wills it; I will it, too.” A. Captier Superior of St. Sulpice |

Monday, March 7, 2011

Biography of Father Martin Callaghan

|

| A drawing of Father Martin Callaghan when young |

|

| Father Martin Callaghan in 1903 |

|

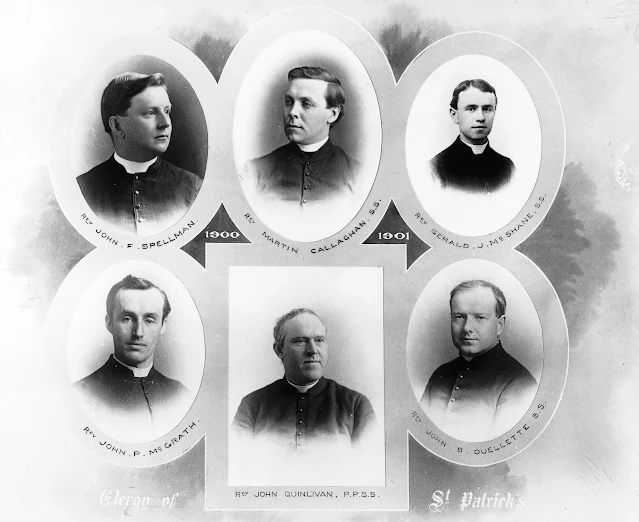

| Photo montage of the pastors at St. Patrick's Church, Montreal; Fr. Martin Callaghan, top middle |

Father Martin Callaghan

In 1915, upon returning to Montreal from Baltimore where he assisted at a funeral for another priest, Father Martin fell ill; this soon developed into congested lungs. Father Martin died on 10 June 1915 in his sixty-ninth year. His brother, Father Luke Callaghan, sang the mass at Father Martin's funeral. One booklet describes the funeral: "A large cortege of mourners accompanied his remains to their last resting place beneath the chapel of the Grand Seminary on Sherbrooke Street."

Father Martin was also an authority Canadian on folklore and for a number of years he was the owner of the Fleming Windmill, an historical landmark located in Ville LaSalle.

His obituary, published in the Montreal Star of 11 June 1915, states that, 'Father Martin,' as he was affectionately known to many, 'was a true Irishman in warmth of heart and breadth of sympathy. His gifts to charitable movements were countless, and many of his benefactions were known only to himself. The poor and needy always found him a ready listener to the story of their troubles.'

Here is an article on Fr. Martin Callaghan from 1915, I have just added the original image of this newspaper article below:

LATE FATHER CALLAGHAN

BELOVED PRIEST,

REV. M. CALLAGHAN

HAS PASSED AWAY

Formerly of St. Patrick’s

Well Known Throughout Province

Good Violinist

And Wrote Music

Authority on Canadian

Folklore—Gave Much

to Charity

The Reverend Martin Callaghan, former…. and [one of the] best known English speaking priests in the Province of Quebec, died last evening at the Hotel Dieu, after an illness of two weeks. He was sixty-nine years old.

Father Callaghan, whose career in the priesthood was long and useful, was born in Montreal, November 1846. He was educated, under the Rev. Father Mayer and the Sulpicians on Sherbrooke Street where after completing his studies he was professor of English for one year, having among his pupils Archbishop Bruchesi of Montreal and Archbishop Langevin of St. Boniface, and many men now prominent in the public life of this Province.

ST MARY’S CURATE

Father Callaghan studied theology under Rev. Fathers Levigne and Colin (?), and was ordained priest by the late Bishop Bourget. He was admitted a member of the Sulpician community in Paris, and began his ministry in Montreal as a curate of St. Mary’s under Father Campion. After one year at St. Mary’s he was appointed to St. Patrick’s under Father Dowd, and afterwards Father Quinlivan, succeeding the latter as pastor of St. Patrick’s. He served for a year under the Sulpician regime under Archbishop Bruchesi.

In December, 1907, after four years service as pastor of St. Patrick’s, Father … resigned to be…pastor…

Father Callaghan was well known as a musician. He was a violin pupil of Oscar Martel, violinist to the late King of Belgium. He was the author of many musical compositions, a number of which were rendered for the benefit of Montreal charities at various times. A deep student of Canadian folklore, his lectures on this subject had been enjoyed by thousands. “Father Martin,” as he was affectionately known to many, was a true Irishman in warmth of heart and breadth of sympathy. His gifts to charitable movements were countless, and many of his benefactions were known only to himself. The poor and needy always found him a ready listener to the story of their troubles.

GAVE AWAY LAND

A year ago he gave a piece of land in the parish of Lachine, which he had purchased some time before as a site for an English-Catholic college, to the Presentation Brothers, for a novitiate. The land was valued at $50,000. Later he gave the same community a site at Longueuil.

As a missionary priest Father Callaghan met with great success, his converts being numbered by thousands. He took special interest in work among the Chinese of Montreal. In collaboration with the Rev. Father Montanard, now serving with the French army, he prepared a Chinese-English catechism.

His brother, the Rev. Luke Callaghan, parish priest of St. Michael’s, was with him at the time of his death, as were his sister Mrs. Farrel, of Lachine, and Rev. Sister Morrissy, and assistants of the parish of Notre Dame.

|

| Fleming Windmill, Montreal, 1900's |

Farmhouse and Fleming windmill, Lasalle, near Montreal, QC, about 1870

In 1815, William Fleming, a Scottish immigrant, built a stone house and a wooden windmill on his property in Lower-Lachine, facing Lac Saint-Louis, near Chemin du Roi (present-day LaSalle Blvd), which was a major thoroughfare and transportation route at the time. He ground barley and rice for local farmers who sold to the Montreal breweries. In 1816, Fleming decided to grind wheat. But this was in direct conflict with the Seigneurial rights of the Sulpician Seminary in Montreal, who had the monopoly on all flour-producing mills since 1663, requiring farmers to have their wheat ground by Sulpician mills for a fee. The Seminary, insisting on their rights, ordered Fleming’s mill to be demolished. Fleming’s lawyers replied that the Seminary had no legal power to rule in Canada. Their status was given by the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Paris, which had no authority in Canada. In 1822,the King’s Bench ruled in favour of the Seminary and ordered non-regulation mills to be demolished. Fleming appealed the decision. Three years later, the eight judges of the Court of Appeal were unable to reach a majority decision, which constituted a victory for Fleming, since, in the absence of a decision, the Montreal Seminary could not force him to demolish his mill. William Fleming took advantage of the victory and decided to rebuild the mill in stone in 1827. He signed a building contract with the mason, William Morrison to build the stone windmill that stands to this very day. From 1827 to the 1880s the ownership and operation of the mill remained within the Fleming family. When William Fleming died in 1860, his son John took over operation of the mill. When activities ceased in the 1880s, the mill’s condition rapidly deteriorated. In 1892, the mill lost two of its blades and the rotating mechanism collapsed. At the turn of the century, the roof and the mechanism had fallen inside the building. After John Fleming’s death, his widow, Isabella Wylie bequeathed the property to Reverend Martin Callaghan, who later transferred the property to Reverend E.P. Curtin. In 1914, Curtin donated the mill to a religious community known as the Presentation Brothers of Ireland. In 1928, The Wellcome Foundation acquired the mill and the surrounding land from the Presentation Brothers of Ireland with the intention of establishing a pharmaceutical company in the area.

Around 1930, the mill and its internal mechanism were restored. As a result of the company’s efforts, the mill was saved from total destruction. In 1947, the City of LaSalle acquired the site from Burroughs Wellcome. Municipal authorities were more concerned about residential and industrial development than about heritage protection, and many old houses were demolished to make room for more modern buildings. In 1976, the Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society convinced the city to apply to the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec, in order to have the mill recognized an official heritage site. They felt that their application was justified even if the millstones and the interior mechanism had disappeared without a trace. In 1982, the city of LaSalle adopted the mill as its official emblem and continued to put pressure on the Quebec government to accelerate the processing of the heritage recognition application. Finally, in 1983, the mill was officially classified as an archaeological heritage site by the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec. After being restored in 1990, it became a historical interpretation centre, open to the public every weekend during the summer. The Fleming Mill is the only windmill of Anglo-Saxon design with a device for turning its sails windward, still standing in the Province of Quebec.

Note: Edited 18 October 2025. This original 1915 newspaper article regarding Fr. Martin's death is below.

Revised: 13 November 2025

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Ten Notes on Thomas D’Arcy McGee

|

| Thomas D’Arcy McGee |

|

| Here I am visiting McGee's mausoleum at Cote des Neiges Cemetery in Montreal. |

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Interview with Poetry Quebec, January 2010

|

| View of Montreal from Pointe-à-Callière, museum, 2017 |

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)