Friday, June 21, 2013

Saturday, June 15, 2013

Fox at Cote des Neiges Cemetery

Monday, June 3, 2013

Monday, May 27, 2013

Thursday, May 23, 2013

Father James Callaghan

|

| Photographs of Fr. James Callaghan, Notman photograph, archived at McCord Museum, Montreal |

Father James Callaghan

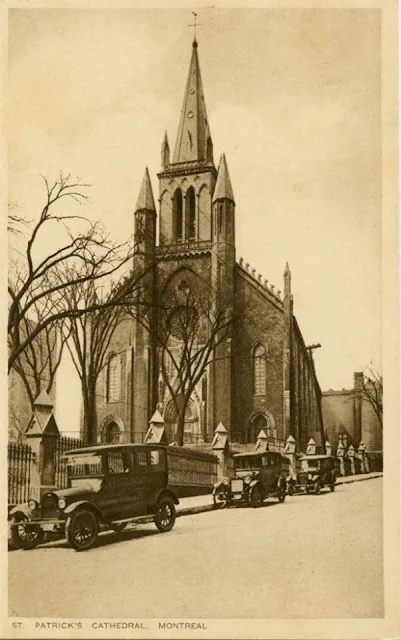

Father Martin's next younger brother is Father James Callaghan. After completing his grade school studies with the Freres des Ecoles chretiennes, James Callaghan (born Montreal, 18 October 1850) studied classics at the College de Montreal (1864-1872). He also studied at the Grand Seminaire de Montreal from 1872-1875, and he completed his studies at the Seminaire Saint-Sulpice de Paris in 1875-1876. After Father James entered the Sulpician Order all of his studies for the priesthood were conducted in France. He became officially a member of the Sulpician Order when he was ordained a priest on 26 May 1877 in Paris. Returning to Montreal, he was the vicar at St. Ann's Church in Griffintown from 1877-1880; this church was demolished in the 1970s but in the late 1990s the foundation was excavated by the City of Montreal and the triangular lot on which the church was located was made into Griffintown-St. Ann's Park. While at St. Ann's Father James lived in the church presbytery at 32 Basin Street in Griffintown. Father James also worked as a professor of English at the College de Montreal (1880-1881). He was a vicar at St. Patrick's (1881-1896) during which time he and his brother Father Martin lived at 95 St. Alexander Street, later they moved to 92 St. Alexander in 1887; 770 Dorchester Street in 1891.

Father James was professor of ecclesiastical studies at the Grand Seminary of Baltimore, Maryland (1896-1897), and in his last years he served as the chaplain at Hotel Dieu Hospital and the Royal Victoria Hospital (1897-1900). He died of kidney failure at Hotel-Dieu Hospital on 7 February 1901, age 51 years. He is described in a church biography as having a beautiful soul, as being innocent and open to other people, full of spontaneity, and as a man who is not guarded or calculating. -o- Here is the official memorial for Fr. James Callaghan from the Sulpician Order: Callaghan, Father James Date of Death: 1901, February

6 Date of

Birth: 1850, October 18 Aix, France March 19, 1901 Fathers and Very Dear in Our Lord: No Memorial Card is Available The huge crowd that Montreal saw gather for the funeral of Father James Callaghan said quite loudly by its presence what affection and what recognition Irish Catholics know how to pay to their priests. It served also as a eulogy on the priestly virtues and sympathetic qualities which our dear departed one had displayed in his ministry, especially during the fifteen years from 1881 to 1896 when he exercised that ministry in the great parish of St. Patrick’s. Father James Callaghan was a child of that parish. He was born there on October 18, 1850, of a faith-filled family which has given three sons to the Church. Even as early as his grade school years with the Christian Brothers he was known for the vivacity of his spirit and for a sunny disposition which never stopped being an important trait of his character. All his life, moreover, exhibited the evidence of a beautiful mind, innocent and uncontaminated, full of spontaneity and of lively impulses which he acted on after thinking them over or weighing the consequences. At the age of fifteen he went to join his brother Martin at the college of Montreal; Martin had preceded him there by three years. There he became a member of a class which has counted twenty-three priests. Amidst so many pious fellow students, the good James distinguished himself less by application to and intensity of work than by the ease with which he did it through a quick and unlabored intelligence, and especially by a character of gold. When he finished his classical course, he unhesitatingly entered the Grand Seminary where the study of sacred sciences roused – even to the point of enthusiasm – that fire of soul which nature and faith together built in him. Ordained subdeacon on May 22, 1875, at the same time as his brother Martin was finishing his year of Solitude, Father James Callaghan soon felt himself attracted to follow his eldest brother to that very place. First, he came with two other confreres to spend a year at the seminary in Paris, entered the Solitude in October 1876, and was ordained priest there on the following May 26th. Some weeks later he brought back to Montreal the first fruits of his priesthood. The first field assigned to his zeal was the Irish parish of St. Anne, still staffed at that time by the priests of St. ___. Among all the works of the holy ministry those on which the young priest especially spent himself with ardor were preaching (for which he was well endowed) and the needs of the young people, whose hearts he very well knew how to win by the liveliness of his faith and his sympathy for their years. After three years of this ministry there was a development which occasioned the trying out of Father James Callaghan as a teacher. St. Anne’s parish and the French parish, St. Joseph’s, were given over by the seminary to diocesan administration. In the new appointments of those who were formerly St. Anne’s priests, Father James was sent to the college as teacher of English. He did good work there and was popular with the youth; but he was subject to distractions and promptings which, considering his duties, were not helpful to the general good order – forgetting sometimes and at other times mistaking the hours of his classes; letting himself, while conducting class, indulge in witty comments on the dry exercises of the day’s lessons, comments which went too far. From the beginning of the school year in 1881, he was given his position of choice, parochial ministry, this time in the mother parish, St. Patrick’s, under the firm and experienced hand of the revered Father Dowd, in whom affection and authority combined to draw out the best of the talents of the young priest. Of this fifteen years of his ministry at St. Patrick’s the Semaine Religieuse of Montreal has said: “To speak of his inexhaustible charity to the poor to whom he was long, by appointment, the dispenser; of his zeal for the instruction and the return to the faith of our separated brothers, of whom he converted a great number; of his dedication to the young, whose works and meetings he oversaw; of the reverence that he always displayed for God’s Word, which he proclaimed with dignity and often with flair; of the retreats without number which he gave to the school children; of the kindness with which at all times he made himself available to everyone – would be superfluous after the magnificent funeral which piety and recognition have given him. At this turnout, how could anyone avoid thinking of the words of the great apostle speaking to the Corinthians – Epistola nostra vos estis quae scitur et legitur ab omnibus homnibus?” (You are our letter, known and read by all?) Those who knew Father Callaghan most intimately have commented on his lively faith, his attachment to St. Sulpice, his obedience to his superiors; and they add that these last two traits especially showed themselves in the last years of his life. I myself, five years ago, experienced that disposition of obedience when I had to ask of Father James Callaghan a sacrifice which could but be keenly felt by him. It was the matter of his leaving his dear St. Patrick’s to go to help out temporarily at the Baltimore seminary, where there was need in Philosophy of a Professor of Holy Scripture and Church History. With no hesitation he assented to my request; went off to Baltimore (as he did everywhere he was assigned), as a good confrere; did his best at his assigned tasks. And when he returned to Montreal the following year, he let himself be placed with the same meekness where his work would be most useful, that is to say, at the Hotel Dieu as chaplain of the sick at that hospital and at the neighboring English hospital. It was in that dedicated ministry (to which he had already been introduced during his time at St. Patrick’s) that he spent the last three years of his life. Without doubt, God had arranged things for him to prepare him for that last journey on which he daily had to act as guide to many poor souls. Many a time during these years he said to his superior: “Don’t be afraid to assign me as you will; I want only to do what you want.” “Some seem to think I want to go back to St. Patrick’s,” he said during the last vacation period. “Leave me at the Hotel Dieu, call me to Notre Dame. I will be happy anywhere you decide I should be.” At that time, he still seemed full of vigor. A little later it was perceived that he was suffering from a severe organic illness, and Father Colin suggested to him to go away for awhile for his health’s sake. The sick man knew that an American bishop who had been his fellow student would welcome him with open arms. But for him that was all the more reason to say: “Please don’t send me there. He would want to keep me with him, and for nothing in the world would I want to leave St. Sulpice.” The kidney disease afflicting him rapidly became fatal. When his stomach and heart became affected, Father Callaghan was visibly wasting away, and our doctor lost the hope that he had at first entertained. Two other doctors, called in for consultation, held the same opinion. The dear patient, however, was not aware of his danger. “I resolved,” wrote Father Colin, “to administer [Extreme Unction] to him while he had still had all his faculties. It was at that time I saw, as never before, all there was of grace and virtue in that beautiful soul reveal itself. On Saturday morning, January 12th, I suggested to him that he prepare himself for his end. ‘First of all,’ he told me, with a pleasant and smiling air, ‘I want to save my soul and give myself to God. Tell me what you want.’ After his confession, which he made with all his heart, he said to me, ‘Take me along with you. I want to be in the seminary infirmary in the midst of my confreres whom I love so much and be near you. It is there I wish to get ready to go, if God calls me.’ I decided nevertheless that it would be wisest for him to stay at the Hotel Dieu, and I told him I would come back between four and five o’ clock. In that visit, I still did not make up my mind to administer [Extreme Unction] to him; but towards eight o’ clock the sisters, quite upset, called me, and I simply told him that it would be more prudent to receive the last sacraments. ‘God wills it, and so do you,’ he told me, ‘so I do too.’ The family, several confreres, several religious, gathered round. He reacted to everything with a kind of happy enthusiasm, with the result that the ceremony was most edifying and touching. The next day, a noticeable improvement was evident, and the doctor once again took hope of keeping him for a while longer; but the improvement was of short duration. “On Wednesday, February 6th, the dear patient, being very ill but still displaying presence of mind, I had him celebrate his [silver] jubilee. The simplicity of his abandonment to God struck me once again as wonderful. The next day he felt better and expressed his joy for the grace received the previous day. At four in the afternoon he spoke of it complacently to Father Quinlivan, who had come to see him. At half past five, his brother Luke, while helping him from his armchair, asked him, ‘Are you all right?’ ‘Yes, I’m all right,’ James answered him. And while saying this, he died without agony. On seeing his head drop, his brother had the presence of mind to give him a final absolution.” When the body was laid out in a parlor of the Hotel Dieu, several thousand visitors came the following days to pray over him. Two days later, on Thursday, February 7th, a first service was sung at the chapel of the house by Bishop Racicot. On Sunday, at five in the evening, the Reverend Superior of Montreal, with an immense crowd on hand, presided at the moving of the body to Notre Dame church, where soon after the Office of the Dead was chanted. On Monday morning at the funeral Mass, sung by Father Leclair in the presence of the many who attended, His Grace, the Archbishop of Montreal, deigned to give the absolution. Later, the burial at the Mountain was conducted by Bishop Emard of Valleyfield, former fellow student of the deceased. Finally, on Wednesday, February 13th, a third Solemn Mass was celebrated at St. Patrick’s by the pastor, and parishioners again came in great numbers to pray for their former assistant and to express their condolences to the worthy family. Father James Callaghan’s old father – who survived him – like us, could not keep from finding such a death very sad and very premature. But with the dear deceased (when his situation was made clear to him), ‘we must all say: “God wills it; I will it, too.” A. Captier Superior of St. Sulpice |

Tuesday, May 21, 2013

Friday, May 17, 2013

Friday, May 10, 2013

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Saturday, April 27, 2013

Review of James Hollis's Creating a Life: Finding Your Individual Path

"Creating a Life: Finding Your Individual Path".

Review of James Hollis' Creating a Life,

Toronto: Inner City Books, 2001. 159 pages.

Sunday, April 14, 2013

duDek and poUnD: six mEsostic poems for dK/

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Morrissey & McGee

At Cote des Neiges Cemetery, a cold day in late March at McGee's mausoleum. Here's the heart someone left hanging on the door to McGee's mausoleum, still there months later...

Sunday, April 7, 2013

Notes on Voice in Poetry

God bless you, Mr. McGee: Thomas D'Arcy McGee, 1813-1868 (two)

Saturday, April 6, 2013

God bless you, Mr. McGee: Thomas D'Arcy McGee, 1813-1868 (one of two)

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Review of Robert Johnson's Balancing Heaven and Earth

Review of Balancing Heaven and Earth

by Robert Johnson, with Jerry M. Ruhl.

1998: Harper Collins, New York. 307 pages

...dreams are the speech of God and that to refuse them is to refuse God... Dreams are highly curative and affirming... you can dialogue (with dreams) and use them to inform your life.

...dreams are the speech of God and that to refuse them is to refuse God... Dreams are highly curative and affirming... you can dialogue (with dreams) and use them to inform your life.

I speak and write of two worlds, when in fact the two are one. To everyday consciousness, however, there is a veil between the Golden World and the earthly world.

I now understand that the most profound religious life is found by being in the world yet in each moment doing our best to align ourselves with heaven, with the will of God.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)