Wednesday, November 5, 2008

St Patrick's Basilica, Montreal (one)

Monday, November 3, 2008

Sunday, November 2, 2008

St. Joseph's Oratory, Montreal (two)

Saturday, November 1, 2008

St. Joseph's Oratory, Montreal (one)

Montreal's St. Joseph Oratory seen from Cote des Neiges Cemetery.

Montreal's St. Joseph Oratory seen from Cote des Neiges Cemetery.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

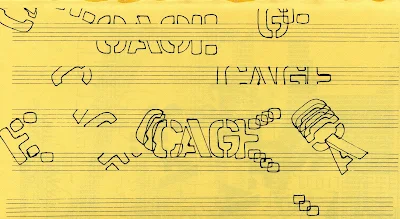

The Cut-up Technique, the Fold-in Technique

I learned of the cut-up method in William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s book Minutes to Go that I read in the early 1970s. I was just beginning to read my work in public and the cut-ups made a huge impression on me at the time. Indeed, the writings of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and William Burroughs, and others, spoke to many of us in a personal and relevant way. Writing poetry was our journey and these older writers were our mentors. I also read all of Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, and other writers that Henry Miller recommended in his The Books in my Life; indeed, that’s where I first heard of Blaise Cendrars and, possibly, J. Krishnamurti. At the time of these early public readings and performances, I was also involved with the writings of John Cage that emphasized silence, randomness, coincidence/synchronicity, and non-linearity in art.

I have always liked several things about making cut-ups: For instance, 1) the physicality (or non-cerebral aspect) of the cut-ups, using scissors and glue to create new writing; 2) the relationship of the cut-ups to making collages, which are really visual cut-ups; 3) I have always been intrigued by the randomness of the cut-ups, allowing a new voice to emerge from the writing; 4) the connection to visual art (painting, film, etc.) interested me; 5) avoiding the imposition of the ego in the writing, always seemed to me one of the objectives I was attempting to achieve in my experimental writing; 6) cut-ups can be performed using several voices, or a room full of voices, or the reading/performance can have several cut-ups read simultaneously.

The cut-ups remind us of a serious ambition in poetry, in sound poetry, in visual poetry, and in printed poetry. In my writing since the cut-ups—writing concerned with redemption and witness—the context has always been living in an existential world in which insight and affirmation of life has been hard-won. The cut-ups affirm life, they show meaning and creativity in randomness and coincidence.

How it works

Preparation: Take two pages of text—which can be your own writing or someone else's—and ensure they have the same line spacing.

Folding: Fold each page in half vertically.

Combining: Place the two folded pages on top of each other.

Reading: Read across the resulting composite page, taking half of the first text and half of the second text for each line.

Temporal shifts: Burroughs used it to create effects like flashbacks by folding page one into page one hundred and placing it as page ten, creating a temporal loop for the reader.

Discovering meaning: Burroughs and Gysin believed the technique could reveal the implicit or "true" meaning of a text by disrupting its linear structure.

Clarity and comprehensibility: Interestingly, Burroughs noted that sometimes the composite text produced by the fold-in method was clearer than the original texts.

Monday, October 27, 2008

The Shaman’s Tune

Shamanism is as old as primeval sea life that has not yet been thrown onto the distant shore of consciousness—consciousness that is about to experience an evolution that takes more years than we can imagine.

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

A Walk on the Lachine Canal

One of the oldest Anglican Churches in Quebec, St. Stephen's Church is just off the canal.

One of the oldest Anglican Churches in Quebec, St. Stephen's Church is just off the canal. Saturday, October 18, 2008

Molsons at Mount Royal Cemetery

Friday, October 17, 2008

Thursday, October 16, 2008

St. Michael's, Mile End, Montreal (two)

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

St. Michael's Church, Mile End, Montreal (one)

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Notes on St. Michael's Church, Mile End, Montreal (two)

|

| Apologies to the photographer; I found this photograph on Facebook and will credit the photographer or remove it on request |