Saturday, September 4, 2010

Thursday, September 2, 2010

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Friday, August 27, 2010

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

Monday, August 23, 2010

The Making of Collages (2)

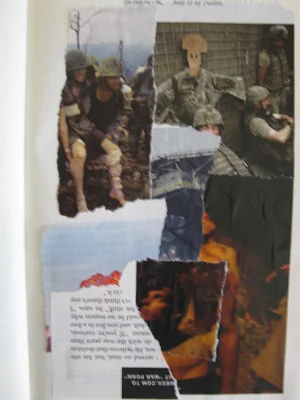

This begins a series of collages--for the next two weeks--made in the winter and spring of 2010. Each collage became, for me, a point of meditation, an insight into the post-modern age.

Each collage is a visual cut-up. The narrative running through our minds of how the world is constructed, how it works, is ended by tearing it into pieces. The random re-organization of these pieces gives us a new narrative, a new insight into how things work.

A longer introduction to The Making of Collages can be found in the posting of last June 28th.

Monday, June 28, 2010

The Making of Collages

A collage juxtaposes images or parts of images that seem to have little association with each other; the collage presents these images in an unexpected and seemingly random way. Profound images, for instance images of human suffering and hurt, become images describing our age. Archetypal images juxtaposed beside each other give a new association, a new idea of the age. The random aspect of the collage is also interesting, this is interesting because any image placed beside any other image gives a third and new image, a new idea or insight coming from the collage. These collages are a kind of Tarot card reading, or divination, of our age, there is the sudden appearance of some insight in the collage.

Collages are similar to Brion Gysin's cut-up technique which works with words and sounds instead of images. I think you could take any issue of TIME magazine, which has excellent photo-journalism, take the images and cut or tear them up at random, and then glue them to a surface in any order that they occur, and you will have a collage that reveals something of the age in which we live. This is what I did with the collages I am putting up here. There is no "thought" in the making of any of these collages. Gradually gluing down the images becomes a system, a process, for instance beginning every collage at the bottom right hand corner, or trying to impose some kind of order or intelligence on the collage as it is being made. When this happens you have to stop and eliminate this thought interference in the making of the collage.

Then, you can also take the collage and ask what does it suggest? What ideas are there in the collage? Archetypal images contain their own energy, their own impetus in driving the unconscious mind. They are an entrance into the collective unconscious and as such they can be very powerful. My suggestion is always to begin with the archetype and then proceed from there; you can try but you can never really defeat the authority of archetypes that are innate in the human psyche.

Friday, April 3, 2009

The Archetypal Field of Poetry

In poetry an archetype, as an image, or as a narrative, gives depth and sophistication to a poem letting it work on several levels of meaning simultaneously. Maud Bodkin, in Archetypal Patterns In Poetry, Psychological Studies Of Imagination (Vintage Books, New York, 1958) examines C.G. Jung’s “hypothesis in regard to the psychological significance of poetry.” She writes,

The special emotional significance possessed by certain poems—a significance going beyond any definite meaning conveyed—he attributes to the stirring in the reader’s mind, within or beneath his conscious response, of unconscious forces which he terms “primordial images,” or archetypes. These archetypes he describes as “psychic residua of numberless experiences of the same types,” experiences which have happened not to the individual but to his ancestors, and of which the results are inherited in the structure of the brain, a priori determinants of individual experience.

An archetype can include psychological complexes—it is a way to analyze and find patterns in any behaviour. Conforti extends the concept of archetypes to posit, if I understand him correctly, an external existence to the archetypes independent of the psyche, or of psychology. Archetypes, for Conforti, are not only psychological constructs, they also have an empirical existence, such as the pattern iron filings on a piece of glass will make when a magnet is placed under the glass. The division between the inner, psychological and spiritual domain, and the outer domain of consensual and empirical reality, is blurred, even eliminated. Conforti’s concept of archetypes seems to be both outside of time and space, and also firmly located in their expression inside the temporal and spatial. It is a fascinating and, some might say, a mystical idea, one that will be rejected by some (or many) clinical psychologists.

While hearing Conforti speak, to the C.G. Jung Society of Montreal last fall (2008), I realized that his concept of archetypes is one of the clues I had been looking for regarding how poetry is composed. It occurred to me that there is an archetypal field of poetry, which does not mean that poems have already been written and poets merely record what they “hear,” although this is what some poets describe as their experience when writing or composing poems. I suggest (and it’s just a thought) that there is an archetypal field of poetry, a psychological state accessed by poets when writing poems. Writing poems is a [“kind-of”] shamanic journey or process in which images (which can also be archetypal) are retrieved and expressed in composition. This should not conflict with the popular division of poets into romantic (or spontaneous) and classical (or formal).

It is very difficult for us to conceive such a thing, but the reality—not just the idea—of the static ego, formed and unchanging, might one day be replaced with a different concept: of a perceiving entity in the active present moment, a constellation of selves with an identifiable Persona, moving in and out of time and space, and possibly existing in the “undifferentiated unity of existence” (W.T. Stace, The Teaching Of The Mystics, Selections From The Great Mystics And Mystical Writings Of The World, A Mentor Book, New York, 1960). We may, one day, conceive of a poem as an existing entity that both exists and doesn’t exist before it is written, and that it comes to us uninvited to be transcribed by the poet. Just as J. Krishnamurti described, during his lectures—including lectures that I attended in Saanen, New York City, and Ojai—that an apparently living entity came to him—not as an invention of his psyche—but as, for instance, a living presence that had a quality of goodness or love that exists outside of his individual consciousness, an entity perceivable at times by him, as existing in the world by itself. There is no “how” as in “how does one access this experience?” There is only the work of creating a foundation for the work to come if it does come or if it is to come.

So, if asked where my poems come from, I would answer that they are from the archetypal field of poetry.

Thursday, March 26, 2009

Instant Shaman (three)

There was a time when I would have agreed with William Everson, certainly one of the major proponents of shamanism in poetry—his famous proclamation for poets is “Shamanize! Shamanize!”—when he writes regarding spirits “… these spirits are collective images, actually we call them today archetypes, but in primitive times they were thought to be separate consciousness.” This makes perfect rational sense. But I also think of work of Dr. Raymond Moody, who is a scholar of the classics, and a doctor of medicine and psychiatry, and whose seminal book Life after Life has had a profound affect on our society’s way of looking at death. A more recent book by Dr. Moody, written with Paul Perry, is Reunions, Visionary Encounters With Departed Loved Ones (Ivy Books, New York, 1993) which describes various techniques of encountering the dead, one of which is mirror gazing. I have heard Dr. Moody speak several times at the annual conferences held in Montreal by the Spiritual Science Fellowship and he is an excellent and fascinating speaker.

On several occasions I have visited mediums and astrologers, and I remember one medium in particular, who told me important information that could not have been known to her, that was specific in detail and importance only to myself, and that gave me immediate relief from what I was concerned about. I have also walked along a street and seemed to feel the presence of spirits walking with me, not of just one or two, but of dozens, so many in fact that it seemed they were pressed up against me. I have also sat with one of the most famous astrologers in the world, Nöel Tyl, and listened while he summarized my life experiences giving not only the year in which experiences occurred but also the exact month, from my birth to the present. Astrology is very different than Spiritualism but both indicate that there is a dimension to existence other than our consensual reality, and we suffer a loss in vision when people rationalize, justify, and excuse away what lies outside the bounds of rational and intellectual thinking.

Another important editor and author on poetry and shamanism is Jerome Rothenberg. I remember the excitement when I first read his anthology of “primitive” poetry Technicians of the Sacred (Anchor Books, New York, 1969). Rothenberg, in his Introduction, writes that the assembled poems show “some of the ways in which primitive poetry and thought are close to an impulse toward unity in our own time, of which the poets are the forerunners.” Then he describes the areas where these intersections of “primitive & modern” occur, one being “the poet as shaman, or primitive shaman as poet & seer thru control of the means… an open ‘visionary’ situation prior to all system-making (‘priesthood’) in which the man creates thru dream (image) & word (song), ‘that Reason may have ideas build on’ (W. Blake).” And in a sidebar he lists the following as examples of this, they are: “Rimbaud’s voyant, Rilke’s angel, Lorca’s duende, beat poetry, psychedelic see-in’s, be-in’s, etc, individual neo-shamanism, works directly influenced by the ‘other’ poetry or by analogies to ‘primitive art’: ideas of negritude, tribalism, wilderness, etc.

In Reunions, Dr. Raymond Moody writes that for the ancient Greeks “visions took place in a state between sleeping and waking.” This psychic state can be accessed by various means, for instance, by mirror gazing, or for the ancient Celts, by gazing into a cauldron of water. Moody has constructed a “psychomateum,” which he describes as “a modernized version of the ones found in ancient Greece, with the same goal in mind, that of seeing apparitions of the dead.” Moody writes,The word psychomateum, taken literally, implies that the spirits of the dead are summoned as a means of divination so that they can be asked questions about the future or other hidden knowledge…the facility I created for this study is not a psychomateum since our purpose was not to arouse the dead for divination. Rather people came (and still come) in hopes of satisfying a longing for the company of those whom they have lost to death…

Regarding shamanism, Moody writes,

In Siberia…Tungus shamans used copper mirrors to “place the spirits.” In their language the word for “mirror” was actually derived from the word for “soul” or “spirit,” and hence the mirror was regarded as a receptacle for the spirit. These shamans claimed to be able to see the spirits of dead people by gazing into mirrors. He also writes, … most people who hear for the first time about shamanism assume that the shamans were either charlatans, mentally ill, or that they possessed some extraordinary faculty that most of us lack. We have already seen that shamans claimed to be able to take voyages into the spirit world through their magic mirrors, where they then saw spirits of the dead… the inner world of those ancient tribal practitioners is accessible to us all.

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Instant Shaman (one)

Back in the early 1970s, when I was a student at Sir George Williams University, I took a line from the French poet Arthur Rimbaud and made it into a visual poem. The poem became a visual representation of the content of Rimbaud’s statement: “regard as sacred the disorder of my mind.” Rimbaud’s approach to poetry is an ancient one, it is also shamanic. When he writes, in Lettres du voyant, “Je est autre,” he becomes the “other,” and we re-vision the poet not only as an individual entity but as a medium for the Divine. God communicates with people through dreams and angels, but communication from the Divine can also occur in a trance state, or in a state of deep relaxation, in a synchronistic experience, in the creative act, or possibly under other heightened conditions of consciousness. This experience is not unfamiliar to many of us who write poetry, for creative people there is often an experience of transcending the ego in the act of creating, and there is usually a sense of wonder that something was created that had not existed before.

My assumption—my intuition—has always been that there is something inherently important in the act of writing poetry. It was Rimbaud’s aim to access the unconscious by entering a trance state, to go beyond or transcend the known by disordering the senses. This could be done, he writes, by «un long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens.» In other words, he would disorder the senses, disorder rational thinking, in order to find the spirit world, the world of archetypes, wherein lies poetry. An important author on this topic is William Everson, author of Birth of a Poet: The Santa Cruz Meditations (ed. Lee Bartlett. Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara, 1982). He writes, “The shaman enters a trance-like condition in order to engage the archetypes (spirits) of the collective unconscious and stabilize their awesome power, appease the demons, as it were. This is precisely the function of the poet today.” He also writes, “…the poet, too, can only work through trance…no creativity is possible that does not involve a trance-like state of possession.” Order exists in the universe, even if it is projected by the human mind, for the mind abhors disorder, craves order, and will create order. I remember as a child lying in bed and seeing faces and shapes in the chintz pattern drapes in my room, or walking along Oxford Avenue to Terrebonne and watching the clouds move across the sky as though they were following me in an intimidating way, or lying on our front lawn and watching the clouds assume the appearance of shapes and faces (this experience, of seeing faces in clouds, is called pareidolia), and I also remember the sound of water dripping from a bathroom tap had the effect of sounding like a voice that was repeating some phrase, over and over again, suggesting some coherent statement.

.jpg)

.jpg)