Back in the early 1970s, when I was a student at Sir George Williams University, I took a line from the French poet Arthur Rimbaud and made it into a visual poem. The poem became a visual representation of the content of Rimbaud’s statement: “regard as sacred the disorder of my mind.” Rimbaud’s approach to poetry is an ancient one, it is also shamanic. When he writes, in Lettres du voyant, “Je est autre,” he becomes the “other,” and we re-vision the poet not only as an individual entity but as a medium for the Divine. God communicates with people through dreams and angels, but communication from the Divine can also occur in a trance state, or in a state of deep relaxation, in a synchronistic experience, in the creative act, or possibly under other heightened conditions of consciousness. This experience is not unfamiliar to many of us who write poetry, for creative people there is often an experience of transcending the ego in the act of creating, and there is usually a sense of wonder that something was created that had not existed before.

My assumption—my intuition—has always been that there is something inherently important in the act of writing poetry. It was Rimbaud’s aim to access the unconscious by entering a trance state, to go beyond or transcend the known by disordering the senses. This could be done, he writes, by «un long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens.» In other words, he would disorder the senses, disorder rational thinking, in order to find the spirit world, the world of archetypes, wherein lies poetry. An important author on this topic is William Everson, author of Birth of a Poet: The Santa Cruz Meditations (ed. Lee Bartlett. Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara, 1982). He writes, “The shaman enters a trance-like condition in order to engage the archetypes (spirits) of the collective unconscious and stabilize their awesome power, appease the demons, as it were. This is precisely the function of the poet today.” He also writes, “…the poet, too, can only work through trance…no creativity is possible that does not involve a trance-like state of possession.” Order exists in the universe, even if it is projected by the human mind, for the mind abhors disorder, craves order, and will create order. I remember as a child lying in bed and seeing faces and shapes in the chintz pattern drapes in my room, or walking along Oxford Avenue to Terrebonne and watching the clouds move across the sky as though they were following me in an intimidating way, or lying on our front lawn and watching the clouds assume the appearance of shapes and faces (this experience, of seeing faces in clouds, is called pareidolia), and I also remember the sound of water dripping from a bathroom tap had the effect of sounding like a voice that was repeating some phrase, over and over again, suggesting some coherent statement.

Showing posts with label shamanism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label shamanism. Show all posts

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Sunday, January 11, 2009

Be Strong: Fight For Your Vision

You have to fight for this life, fight for your vision. Fight to stay alive and creative and breathing, filling your two lungs to capacity and then letting the air out in giant breaths of poetry; breathe in that life is good, life is good, life is good. Be grateful for each breath and feel life moving through your body; breathe out the great breaths of poetry, speak love, speak the words of your vision that keep you alive, and in all things it’s a fight for your vision, your voice, your love for this life.

Monday, November 17, 2008

Saturday, November 15, 2008

Shamanism and Poetry

From Janet O. Dallett's When the Spirits Come Back (Inner City Books, Toronto, 1988); she writes:

Reflecting upon these events, I understood for the first time that a certain kind of work, resembling what Jung calls "visionary art," functions in much the same way as the shaman in tribal societies. That is, some art is shamanic in function. Formed from the collective unconscious material, it activates the unconscious of its audience and mobilizes the psyche's self-healing capacities. It opens a door to a different reality, the world of dreams and imagination, and "spirits" silently pass into the world of every day, affecting people in unexamined ways.

Shamanic art undermines unexamined cultural assumptions. For this reason it disturbs some people and may even arouse rage. Those who are open to it, however, often find that it sets their own creativity in motion.

Such art tends to be prophetic. It asks, even insists, on being heard, just as shamans are compelled to tell about their inner experiences when they begin to apply what they have learned about healing themselves to their healing of others. The visionary creative act is not complete until it finds an audience, coming out into the world and disturbing the complacent surface of collective consciousness. If the process is blocked, one outcome may be psychosis. Cancer may be another.

Shamanic art brings eros values to the healing of the psyche. That is, unlike traditional clinical psychology and psychiatry, it is more concerned with connecting and making whole than with the logos values of dissecting and understanding. It is related to a form of psychotherapy that interprets rarely, seeking instead to set in motion a symbolic process that has its own unforseeable healing goal. Understanding of behaviour is important only to the extent that it serves a living relationship to deep levels of the psyche. . . The soul of the shaman lies equally behind the visionary artist and the therapist who works in this way. If the shamanic type of therapist ceases to live her own creative life, the capacity to function in healing ways becomes lost and may even turn destructive. (36 - 37)

Friday, November 14, 2008

Shamanism and Poetry, some definitions (One)

(from) Earth Household, by Gary Snyder:

The Shaman-poet is simply the man whose mind reaches easily out into all manners of shapes and other lives, and gives song to dreams. Poets have carried this function forward all through civilized times; poets don’t sing about society, they sing about nature—even if the closest they ever get to nature is their lady’s queynt. Class-structured civilized society is a kind of mass-ego. To transcend the ego is to go beyond society as well. “Beyond” there lies, inwardly, the unconscious. Outwardly, the equivalent of the unconscious is the wilderness: both of these terms meet, one step further on, as one. (122)

Notes made around 1968 from televised lectures by Allan Watts, On Living:

Religious man of hunting cultures is a shaman.

Magic from going alone in the forest.

The priest, Brahman, has a guru; the shaman is alone with

animals & trees, knows rocks are alive.

Watts is a shaman, an Anglican minister “I gave it up.”

Offended at the notion of telling God what he already knows—

that I’m a miserable sinner. No religion or society,

but sympathy for all.

(from) Letters of Arthur Rimbaud:

May 13, 1871: …I want to be a poet… I am working to make myself a visionary…To arrive at the unknown through the disordering of all the senses, that’s the point. The sufferings will be tremendous, but one must be strong, be born a poet: it is in no way my fault.

May 15, 1871: … The first study for a man who wants to be a poet is the knowledge of himself, entire. He searches his soul, he inspects it, he tests it, he learns it. As soon as he knows it, he cultivates it: it seems simple: in very brain a natural development is accomplished; so many egoists proclaim themselves authors; others attribute their intellectual progress to themselves! But the soul has to be made monstrous, that’s the point:… like comprachios, if you like! Imagine a man planting and cultivating warts on his face.

One must, I say, be a visionary, make oneself a visionary.

The Poet makes himself a visionary through a long, a prodigious and rational disordering of all the senses. Every form of love, of suffering, of madness; he searches himself, he consumes all the poisons in him, keeping only their quintessences. Ineffable torture in which he will need all his faith and superhuman strength, the great criminal, the great sickman, the accursed—and the supreme Savant!

…kindly lend a friendly ear and everybody will be charmed…

So, then, the poet is truly a thief of fire.

Humanity is his responsibility, even the animals…

Baudelaire is the first visionary, king of poets, a real God!

Monday, October 27, 2008

The Shaman’s Tune

Shamanism is as old as primeval sea life that has not yet been thrown onto the distant shore of consciousness—consciousness that is about to experience an evolution that takes more years than we can imagine.

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Friday, September 5, 2008

The Shaman’s Way

Years ago—in the early 1970s—my brother gave me a large woodcut entitled “A shaman on the back of a grizzly.” I had this on my bedroom wall, in different bedrooms, for many years. Looking back now, I see how important shamanism has been to my creative, spiritual, and personal life. In fact, it was staring down at me all those years ago. Shamanism is mankind’s oldest form of spirituality. It is the spirituality of our most distant ancestors.

The shamanic journey—the shamanic way—gives cohesion and meaning to pivotal experiences in my life. I do not renounce my western traditions or my life in the 21st Century, but I can better understand my own existence, my concerns in poetry, because of shamanism. Shamanism does not displace the contemporary, it deepens and widens and co-exists with our understanding of the contemporary. As well, shamanism has helped me to understand experiences I have had; it has helped me to better understand my own life, spirituality, and what I had intuited from an early age regarding my concerns as a poet. Let’s just say, shamanism was always in my unconsciousness, waiting to surface, like ancestral memories.

The image of the shaman on the back of a grizzly—the image on the woodcut—entered my psyche and, looking back, became a part of my inner being. It made a deep enough impression on me at the time that, in 1972 or 1973—probably not long after I was given the woodcut—I wrote a poem, “a shaman on the back of a grizzly,” using the woodcut as a narrative for the poem. The shaman sitting on the back of a grizzly bear, incongruously almost as big as the grizzly; always riding “bear back”; always staring directly at the viewer; always the expression of surprise and worry on the shaman’s face; the shaman and the bear always appearing from some unknown and unknowable psychic place and always departing to some other place that is unknown and unknowable, and always in the continuum of existence.

“a shaman on the back of a grizzly”

a shaman on the back of a grizzly

the black fur a black streak

moving between the trees

then across an open grassy field

a shaman eyes blackened

hair hanging limply down over ears

& arms holding to handfuls of bearskin

he leans slightly forward

knees pressing to flanks

the grizzly face down & mouth open

a bewildered look on his face

we see the white of his teeth

we see the shaman mouth open

we see him see us

we see them disappear back into the forest

they see us disappear back into the forest

we see them disappear back into the forest

we see him see us

(1972-1973)

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

A Statement: All Art is Vision

After seeing Huichol yarn paintings in Galeria Uno in Puerto Vallarta: The art of the Huichol shaman is created only when in a peyote trance vision. All art, then, is vision. This is different from the way most art is created by Western artists who are in the grip of the “art production assembly line."

For many years I searched for this clue to my own approach and understanding of art. It is what I intuited in late 1960s when I began experimenting in my writing, when I attempted to write outside of the narrow linear and rational mind, when I was absorbed in experiments attempting to short circuit the rational mind. Now a shamanic approach has been articulated to me, an approach that I can identify with.

I place my heart in the visionary’s approach. My identification of myself as a poet has always been outside of the mainstream of the poetry community. I was never very much a part of any poetry community as they rarely expressed my concerns in poetry.

Written on 19 November 1984, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico; Huntingdon, 1991; Montreal, 2008.

For many years I searched for this clue to my own approach and understanding of art. It is what I intuited in late 1960s when I began experimenting in my writing, when I attempted to write outside of the narrow linear and rational mind, when I was absorbed in experiments attempting to short circuit the rational mind. Now a shamanic approach has been articulated to me, an approach that I can identify with.

I place my heart in the visionary’s approach. My identification of myself as a poet has always been outside of the mainstream of the poetry community. I was never very much a part of any poetry community as they rarely expressed my concerns in poetry.

Written on 19 November 1984, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico; Huntingdon, 1991; Montreal, 2008.

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

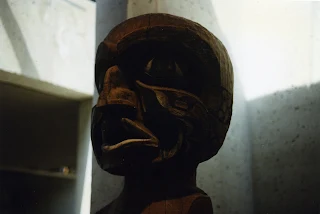

The Mystic Beast

At the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia. I liked this statue so much I used drawing of it, by Ed Varney, on the cover of my book, The Mystic Beast.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)