|

Apologies to the photographer; I found this photograph on Facebook and will credit

the photographer or remove it on request |

As in a previous visit, the church was open to the public during the day. Inside the church, there was only a student guide, an older man washing the floors, and myself. I sat in one of the pews close to the altar and thought about Father Luke; his great accomplishment was certainly building and running this church. St Michael’s has a seating capacity for 1400 people and when additional seating had to be used, folding chairs were placed in the center aisle. St. Michael’s was once the largest English-speaking parish in the province of Quebec with 1,809 families attending the church and close to 15,000 parishoners.

Father Luke Callaghan was a unique man; indeed, he was a visionary. He helped raise the money to build St. Michael’s, he was instrumental in the choice of architecture for the church, as well as the choice of stained glass windows and interior decorations. Looking at the paintings by Guido Nincheri that decorate the interior of St. Michael’s, you will see some of the most interesting church art in Quebec. There is also the marble facing on the walls, and a painting on the interior of the church dome of St. Michael the Archangel. It seems no expense was spared in the building and interior decoration of this incredible church!

I used to think that St. Michael’s was in some ways a folly of Father Luke’s, as the church is a copy of Hagia Sophia (Greek for Holy Wisdom) in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), Turkey. However, it isn’t unusual to copy famous churches on a reduced scale. For instance, Mary, Queen of the World Cathedral, located on Boulevard-René Lévesque (formerly Dorchester Boulevard) near the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, is a smaller version of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

Hagia Sofia began as a church in Constantinople; it was rededicated in 537 AD and was (and probably still is) one of the largest churches in the world. In 1453 Constantinople and Hagia Sofia fell into Muslim hands. Constantinople became Istanbul and Hagia Sofia became a mosque. In 1935, Kemal Ataturk, the reformer of modern-day secular Turkey, converted Hagia Sofia into a museum. Recently Pope Benedict XVI visited Istanbul and Hagia Sophia and the building still resonates with historical and spiritual importance.

There must be a “story” as to why Father Luke decided to build St. Michael’s church in a Greek Orthodox design. There is really no other church in Quebec like St. Michael’s with its turret just to the right and behind the poured concrete dome. The student guide informed me that the turret, which is 160 feet high, was originally the church’s bell tower but this use had to be abandoned as they were afraid the turret might collapse. The copper dome outside has also recently been cleaned, so it now has a shiny, almost golden appearance when reflecting the bright summer sun.

Inside of the church, on the inside of the dome, as one stands and looks up, there is a painting of Michael the Archangel, large wings behind him, standing on the dragon that he has just slain, The painting is magnificent, set in a circle in the dome, then there are two outer circles: the first outer circle seems to contain many faces whose significance is not apparent. Then, after some patterned decoration, there is a third circle of angels each with a distinct personality. Also, a repeated pattern of decoration is found throughout the church, the pattern is a painting of a dragon with a sword thrust through it, no doubt the work of St. Michael. The art is original and inspired and there are many other delightful embellishments throughout the church.

Additionally, there are two very large half rosette stained glass windows facing each other on the east and west sides of the church. There is a kind of shamrock design to the eight outer windows, then nine large windows are set between these, and a final shamrock at the bottom, all in a huge semi-circle. The same window design is found on either side of the church, it is non-representational, and almost art nouveau in appearance. A traditional stained glass window would have been out of place in the church.

If you stand at the front of the church, at the altar, you can look across the whole expanse of the church and pews, to the second floor balcony where the organist would sit, and more pews, and then a large round stained glass window of eight shamrock patterns circling a center design. When the sunlight enters the church these window are a veritable glowing fountain of light. It is unfortunate that the church itself, perhaps because of its size and that the windows are set so high on the walls, is in relative darkness most of the time, and this gives it a rather gloomy feeling. The altar is unfortunately also in darkness because of the absence of natural lighting, but I assume there is auxiliary lighting that can illuminate the entire church.

Again, as you stand at the altar and look across the church, seeing the balcony and the main floor, there is a painted decoration on the wall between the floors, of a repeated pattern of a dragon impaled by a sword. The sword, of course, also suggests a cross and the dragon or serpent reminds one of the serpent in the Garden of Eden, symbolic of man’s fallen state. The interior condition of the church, the painted walls and ceiling, is still very good, suggesting that the art may be frescoes, or alternatively that there has been little water or other damage over the years. The dimensions for size of the windows is suggested by the size of the dome: the half dome measures 52 feet in diameter, the full dome 75 feet in diameter, with 24 windows.

On the main floor, at the entrance to the church, there are three doors, with a glass semi-circle of shamrocks over each door, almost like transoms. If you stand just inside of the church entrance and look upwards at the ceiling, you will see written in Latin some names, among them “Pope Benedicto XV”, “Archbishop Paulo Bruchesi”, and “Luca Callaghan.” Other names can also be found in the other groupings of names on the ceiling.

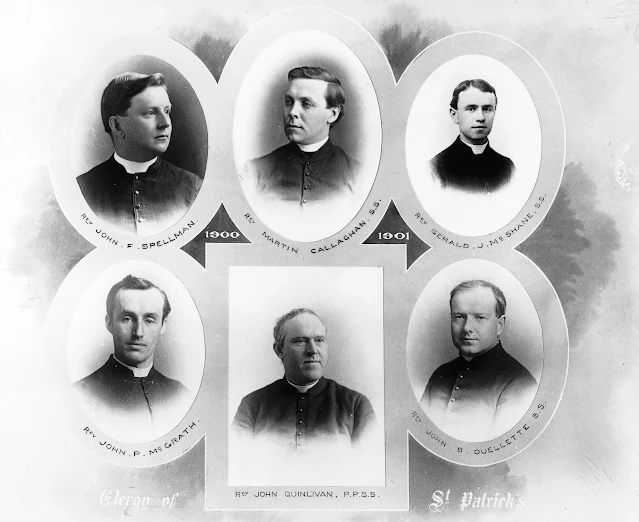

Father Luke Callaghan was a great administrator, a pastor who guided his many parishoners and constructed and then ran St. Michael’s for twenty-one years, from 1910 to 1931. I am not personally convinced that copying Hagia Sofia was the greatest idea, but it was certainly an original idea. Sitting in St. Michael’s that July day, I had a growing admiration for Father Luke. His sights were set on greatness, and he accomplished a great feat in building St. Michael’s Church. He was a scholar, had earned a Ph.D. in Rome, and had an important posting at the Archbishop’s Palace in Montreal on LaGauchetiere Street. He is a man who accomplished much because of his intelligence, his commitment to hard work, his sense of responsibility to his congregation and the Church. Not as colourful as his older brother, Father Martin Callaghan, he was nevertheless a man of great substance and determination.

%20at%20Luke%20Callaghan%20Memorial%20High%20School,%201.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20at%20Luke%20Callaghan%20Memorial%20High%20School,%202.jpg)

.jpg)