Thursday, March 31, 2011

A walk in NDG (five)

Here we are on the Loyola Campus of Concordia University, a statue of Mary near the Psychology Department.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Review of James Hollis's On this Journey ...

On This Journey We Call Our Life: Living the Questions,

Review by Stephen Morrissey

Other than saying that psyche is the totality of who we are—blood, brain, viscera, history, spirit and soul—we cannot limit its meaning. Note that psyche comes from two etymological roots: that of breathing, suggestive of the invisible life force which enters at birth and departs at death; and that of the butterfly, suggesting a teleologically driven process of evolution and transformation, which in the end is both beautiful and elusive... While we may be tempted to romanticize psyche as the place of sweet dreams, it is also the source of devouring energies, self-destruction and demonic drives.

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

My drive home from work in March 2011(five)

|

| Departure... |

|

| On the Champlain Bridge... |

|

| On the Decarie Expressway... |

|

| Downtown Montreal in the distance... |

|

| My exit... |

|

| Getting off at the Sherbrooke Street exit, then west on Sherbrooke and home... |

Saturday, March 26, 2011

Lost, found, missing... (four)

Looking at these posters for lost, sometimes found, sometimes still missing pets--and occasionally missing people--the images taken in happier days become images of sadness, grief, and loneliness. A new context for presenting the image, in a poster, changes the meaning of the image from one of love and happiness to a context of loss.

We transform our pets into surrogate children, surrogate partners--we place a human burden on them--and yet, obviously, we don't value them as much as we value humans, there are few, or no posters for lost children. There is a poignancy to the images. As the image ages, it becomes damaged by water, faded by sunlight, and hope of finding the lost pet is diminished. The pet stares back at us, lost, sometimes found, missing.

Friday, March 25, 2011

Dr. William P. Morrissy of Greenpoint, Brooklyn

|

Here is a photograph of Dr. William P. Morrissy of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY. The photograph is undated, an approximate date would be mid-1880s to mid-1890s. The photograph was sent to me by Anthony Sutherland. Dr. Morrissy was a nephew of my great great grandfather, Laurence Morrissey. William's brother, John Veriker Morrissy, was a Member of Parliament for Northumberland riding in New Brunswick. William was one of the first police surgeons for New York City. It is William's letter, written when he was a boy still living in New Brunswick, to Laurence Morrissey, by then living in Montreal, that contains so much information on the Morrissey family that the letter was saved for future generations; somehow it was even returned to the family in Newcastle (Miramichi), NB. More can be found on William at http://www.morrisseyfamilyhistory.com/. |

Thursday, March 24, 2011

Monday, March 21, 2011

Thursday, March 17, 2011

Monday, March 14, 2011

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Monday, March 7, 2011

Biography of Father Martin Callaghan

|

| A drawing of Father Martin Callaghan when young |

|

| Father Martin Callaghan in 1903 |

|

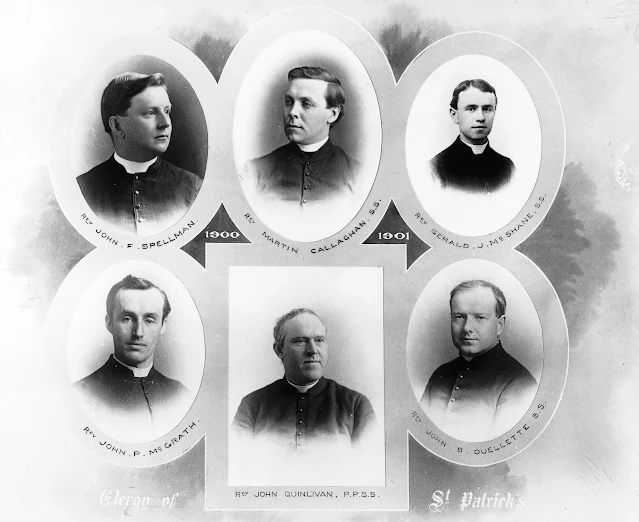

| Photo montage of the pastors at St. Patrick's Church, Montreal; Fr. Martin Callaghan, top middle |

Father Martin Callaghan

In 1915, upon returning to Montreal from Baltimore where he assisted at a funeral for another priest, Father Martin fell ill; this soon developed into congested lungs. Father Martin died on 10 June 1915 in his sixty-ninth year. His brother, Father Luke Callaghan, sang the mass at Father Martin's funeral. One booklet describes the funeral: "A large cortege of mourners accompanied his remains to their last resting place beneath the chapel of the Grand Seminary on Sherbrooke Street."

Father Martin was also an authority Canadian on folklore and for a number of years he was the owner of the Fleming Windmill, an historical landmark located in Ville LaSalle.

His obituary, published in the Montreal Star of 11 June 1915, states that, 'Father Martin,' as he was affectionately known to many, 'was a true Irishman in warmth of heart and breadth of sympathy. His gifts to charitable movements were countless, and many of his benefactions were known only to himself. The poor and needy always found him a ready listener to the story of their troubles.'

Here is an article on Fr. Martin Callaghan from 1915, I have just added the original image of this newspaper article below:

LATE FATHER CALLAGHAN

BELOVED PRIEST,

REV. M. CALLAGHAN

HAS PASSED AWAY

Formerly of St. Patrick’s

Well Known Throughout Province

Good Violinist

And Wrote Music

Authority on Canadian

Folklore—Gave Much

to Charity

The Reverend Martin Callaghan, former…. and [one of the] best known English speaking priests in the Province of Quebec, died last evening at the Hotel Dieu, after an illness of two weeks. He was sixty-nine years old.

Father Callaghan, whose career in the priesthood was long and useful, was born in Montreal, November 1846. He was educated, under the Rev. Father Mayer and the Sulpicians on Sherbrooke Street where after completing his studies he was professor of English for one year, having among his pupils Archbishop Bruchesi of Montreal and Archbishop Langevin of St. Boniface, and many men now prominent in the public life of this Province.

ST MARY’S CURATE

Father Callaghan studied theology under Rev. Fathers Levigne and Colin (?), and was ordained priest by the late Bishop Bourget. He was admitted a member of the Sulpician community in Paris, and began his ministry in Montreal as a curate of St. Mary’s under Father Campion. After one year at St. Mary’s he was appointed to St. Patrick’s under Father Dowd, and afterwards Father Quinlivan, succeeding the latter as pastor of St. Patrick’s. He served for a year under the Sulpician regime under Archbishop Bruchesi.

In December, 1907, after four years service as pastor of St. Patrick’s, Father … resigned to be…pastor…

Father Callaghan was well known as a musician. He was a violin pupil of Oscar Martel, violinist to the late King of Belgium. He was the author of many musical compositions, a number of which were rendered for the benefit of Montreal charities at various times. A deep student of Canadian folklore, his lectures on this subject had been enjoyed by thousands. “Father Martin,” as he was affectionately known to many, was a true Irishman in warmth of heart and breadth of sympathy. His gifts to charitable movements were countless, and many of his benefactions were known only to himself. The poor and needy always found him a ready listener to the story of their troubles.

GAVE AWAY LAND

A year ago he gave a piece of land in the parish of Lachine, which he had purchased some time before as a site for an English-Catholic college, to the Presentation Brothers, for a novitiate. The land was valued at $50,000. Later he gave the same community a site at Longueuil.

As a missionary priest Father Callaghan met with great success, his converts being numbered by thousands. He took special interest in work among the Chinese of Montreal. In collaboration with the Rev. Father Montanard, now serving with the French army, he prepared a Chinese-English catechism.

His brother, the Rev. Luke Callaghan, parish priest of St. Michael’s, was with him at the time of his death, as were his sister Mrs. Farrel, of Lachine, and Rev. Sister Morrissy, and assistants of the parish of Notre Dame.

|

| Fleming Windmill, Montreal, 1900's |

Farmhouse and Fleming windmill, Lasalle, near Montreal, QC, about 1870

In 1815, William Fleming, a Scottish immigrant, built a stone house and a wooden windmill on his property in Lower-Lachine, facing Lac Saint-Louis, near Chemin du Roi (present-day LaSalle Blvd), which was a major thoroughfare and transportation route at the time. He ground barley and rice for local farmers who sold to the Montreal breweries. In 1816, Fleming decided to grind wheat. But this was in direct conflict with the Seigneurial rights of the Sulpician Seminary in Montreal, who had the monopoly on all flour-producing mills since 1663, requiring farmers to have their wheat ground by Sulpician mills for a fee. The Seminary, insisting on their rights, ordered Fleming’s mill to be demolished. Fleming’s lawyers replied that the Seminary had no legal power to rule in Canada. Their status was given by the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Paris, which had no authority in Canada. In 1822,the King’s Bench ruled in favour of the Seminary and ordered non-regulation mills to be demolished. Fleming appealed the decision. Three years later, the eight judges of the Court of Appeal were unable to reach a majority decision, which constituted a victory for Fleming, since, in the absence of a decision, the Montreal Seminary could not force him to demolish his mill. William Fleming took advantage of the victory and decided to rebuild the mill in stone in 1827. He signed a building contract with the mason, William Morrison to build the stone windmill that stands to this very day. From 1827 to the 1880s the ownership and operation of the mill remained within the Fleming family. When William Fleming died in 1860, his son John took over operation of the mill. When activities ceased in the 1880s, the mill’s condition rapidly deteriorated. In 1892, the mill lost two of its blades and the rotating mechanism collapsed. At the turn of the century, the roof and the mechanism had fallen inside the building. After John Fleming’s death, his widow, Isabella Wylie bequeathed the property to Reverend Martin Callaghan, who later transferred the property to Reverend E.P. Curtin. In 1914, Curtin donated the mill to a religious community known as the Presentation Brothers of Ireland. In 1928, The Wellcome Foundation acquired the mill and the surrounding land from the Presentation Brothers of Ireland with the intention of establishing a pharmaceutical company in the area.

Around 1930, the mill and its internal mechanism were restored. As a result of the company’s efforts, the mill was saved from total destruction. In 1947, the City of LaSalle acquired the site from Burroughs Wellcome. Municipal authorities were more concerned about residential and industrial development than about heritage protection, and many old houses were demolished to make room for more modern buildings. In 1976, the Cavelier-de-LaSalle Historical Society convinced the city to apply to the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec, in order to have the mill recognized an official heritage site. They felt that their application was justified even if the millstones and the interior mechanism had disappeared without a trace. In 1982, the city of LaSalle adopted the mill as its official emblem and continued to put pressure on the Quebec government to accelerate the processing of the heritage recognition application. Finally, in 1983, the mill was officially classified as an archaeological heritage site by the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec. After being restored in 1990, it became a historical interpretation centre, open to the public every weekend during the summer. The Fleming Mill is the only windmill of Anglo-Saxon design with a device for turning its sails windward, still standing in the Province of Quebec.

Note: Edited 18 October 2025. This original 1915 newspaper article regarding Fr. Martin's death is below.